'All Change'

Bradford's through railway schemes

John Thornhill

(First published in 1986 in volume 2, pp. 35-46, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

1830-1846: Bradford's First Railway

Trains were not cheered into Bradford until 1846, twenty-one years after the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. But in 1830 Bradford businessmen, inspired by the success of Liverpool & Manchester Railway's passenger service, submitted a Bill for a line to Leeds and Temple Newsam, where it would join the Leeds & Selby Railway, and so gain access to a sea route. The first mile or so of this line was to be cable-operated, up the incline from Bradford to Laisterdyke, but nothing came of the scheme.

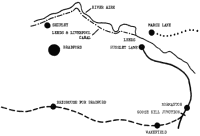

Ten years passed without much progress, but on 5 October 1840 the Manchester & Leeds brought trains within striking distance of Bradford by opening a line between Hebden Bridge and Normanton (Fig. 1). At Brighouse Station the name board proclaimed 'Brighouse for Bradford', which meant that Bradford passengers faced either a seven-mile walk or an hour's journey by coach or carrier's cart before reaching home. The route into Leeds was by way of a junction with the North Midland at Goose Hill and then to Hunslet Lane Station.

In 1843 another group of businessmen, disappointed with past failures, planned a line linking Bradford with Leeds and the North Midland. George Hudson, the 'Railway King', who was chairman of the North Midland, asked Robert Stephenson, their chief engineer, to undertake a survey. Stephenson made two surveys, one for a direct line through Stanningley, the 'Short Line', and another via Shipley and the Aire Valley, which had been recommended by his father, George Stephenson, four years earlier.

The Bill for the Leeds & Bradford Railway, based on the Aire Valley survey, proposed that the line should run from Leeds, near Wellington Street, to a station off Kirkgate in Bradford (Fig. 1). Included in the Bill were as yet undefined plans for a line through Bradford to Halifax and the Calder Valley, where it would join the Manchester and Leeds Railway.1

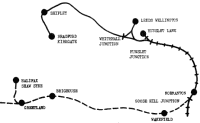

Strenuous opposition to the Aire Valley plan came from both the 'Short Liners' and the Manchester & Leeds, who by this time had constructed their own line to Goose Hill, south of Normanton (Fig. 2). From there they made use of the North Midland line into Leeds, because Parliament had refused to sanction two parallel tracks. The Manchester company, who were by now very eager to secure an alternative and more direct route to Leeds, threw their weight behind the Short Line party, who were campaigning for a railway from Bradford to Leeds via Stanningley. In spite of all opposition, however, the Leeds & Bradford obtained its Act on 4 July 1844, on a promise to make the additional line mentioned above, that is through Bradford to a junction with a future railway running from Halifax to Sowerby Bridge.2

On 10 May 1844 the Midland Railway had come into being through an amalgamation of three companies, the North Midland, the Birmingham & Derby Junction and the Midland Counties. The second and third of these were impecunious lines whose cut-throat competition had brought them near to bankruptcy. The Midland eventually embarked on a policy of expansion which made it one of the greatest of the pre-Grouping Railways.

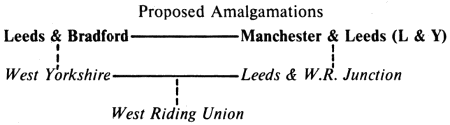

In 1844, in order to implement its promise regarding a through line, the Leeds & Bradford formed a subsidiary, the West Yorkshire Railway, with the aim of constructing what became known as the Bradford Connecting Lines, along with several others to the south and east of the town. Towards the end of the year the Manchester & Leeds formed the Leeds & West Riding Junction Railway for the purpose of building lines similar to those of the West Yorkshire, and both companies deposited their Bills.

Meanwhile John Hawkshaw, chief engineer of the Manchester & Leeds, surveyed the area and expressed his regret that the Leeds & Bradford refused to indicate the precise position of its station in Bradford. However, he finally offered alternative lines entering from the direction of Bridge Street. The first track, graded 1 in 63, would come down into the town at ground level, and the second would be carried on an embankment across the town to join the Aire Valley line at Manningham.

1845 saw the parliamentary contest between the West Yorkshire and the Leeds & West Riding Junction. On 9 May the former's Bill, which included the Connecting Lines was rejected, but the preamble to the Leeds & West Riding Bill was proved, and passed through the Commons only to be defeated in the Lords. Robert Stephenson then recommended an amalgamation of the two competing railways and by July 1845 plans for the formation of the West Riding Union Railway were well in hand.3

At this time, as prospective holders of one-quarter of the West Riding Union Stock, the Leeds & Bradford agreed to apply for powers to build connecting lines through the town centre on a viaduct rising from zero at Bolton Lane, Manningham, to about 25 feet at the point where an end-on junction would be made with the West Riding Union at Well Street/Dunkirk Street.4

In November 1845, perhaps despairing of the 'Short Line' scheme, and still anxious to get an alternative way into Leeds, the Manchester & Leeds took the unexpected step of proposing amalgamation with the Leeds & Bradford. The latter accepted the proposal in principle, and the two parties and representatives of the Midland Railway met at Hunslet Lane Station on 27 December, when they agreed to obtain parliamentary approval of their plan.

The opening of the Leeds & Bradford Railway took place on 1 July 1846 - an auspicious day for Bradford. Sixteen years had elapsed since the first attempt to link the two towns.

1846-1883: Plans for Connecting Lines

Three Bills now came before the Parliamentary Committee:

- For the West Riding Union Railway.

- For the Leeds & Bradford-Manchester & Leeds amalgamation.

- For the Bradford Connecting Lines.

The West Riding Union received its Act on 3 August 1846, by which time the proposed amalgamation between the two parent companies themselves had fallen through. A disagreement as to the interpretation of clauses had resulted in the disenchanted Leeds & Bradford offering itself to the Midland Railway, and the terms of lease had been quickly arranged. It was petty quarrels like these that determined the fate of railways through Bradford. The Midland purchased the Leeds & Bradford outright in 1851 and thereby took the first tentative step towards Carlisle.

On 16 August 1846 the Royal Assent was given to the Leeds & Bradford's Connecting Lines Act:

"A BILL for enabling the Leeds & Bradford Railway to make a junction line at Bradford. . . and whereas it is expedient the said Leeds & Bradford Railway should be authorised to make and maintain an additional line of railway over, upon or alongside a portion of the present line of railway now in course of construction, and at a different level from the present line of railway from a point in the Township of Manningham near Bolton Lane to or near Well Street in the Township and Parish of Bradford, there to form a junction with the proposed line of the West Riding Union Railway."

The phrases 'over, upon or alongside' and 'at a different level' appear to give plenty of constructional scope. The Act further authorized the closure of School Street to vehicular traffic, pedestrians being served by a footbridge. It also gave powers for the leasing of the Connecting Lines to the Midland or the Manchester & Leeds. The Midland, in effect, always had these lines within their grasp but chose to allow the powers to lapse - a sad decision which was later regretted.

In 1847 the Manchester & Leeds was re-named Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, and as such is known in the remainder of this article.5

Another attempt to put Bradford on a through line was made in 1865, when the four railways serving the town joined forces to unite all passenger facilities in a common central station. The Lancashire & Yorkshire was the driving force, and it seems likely that the great inconvenience of operating the ramshackle Exchange Station had prompted its owners to opt for a new station on another site, thus connecting all the existing railways. This project failed when three of the companies, including the Midland, withdrew, and the survivor, the Lancashire & Yorkshire, was unable to raise the required capital of £260,000.

In 1883 the Midland Board invited the Town Clerk of Bradford to visit Derby to consider yet another scheme for a line through the town centre. This time the Bradford Central Railway, sponsored by the Town Council and the Chamber of Trade, proposed to build a passenger station connecting all three of the railways serving the borough. Nothing came of the Town Clerk's visit.

1894-1919: West Riding Lines and Bradford Through Lines Acts

The most ambitious of all the through line schemes, and certainly the most thorough, was the result of a deputation from a number of West Riding towns to the Midland Board at Derby in 1894. The Midland's main line, after leaving Sandal, went round the industrial heart of the West Riding, passing up the Aire Valley to Leeds and Shipley. Within this region, Huddersfield, Halifax, Dewsbury and a number of smaller towns, were all seeking northsouth outlets for passengers and goods. The Midland Board, knowing what rich pickings were available, met the deputation to discuss possible routes.

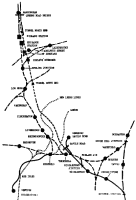

1896 was a year of promise. At a meeting of Midland shareholders held at Derby in February, the Chairman, Sir Ernest Paget, spoke at length about a new line for which a Bill had been prepared, and stressed the need for a railway going in a north-westerly direction through the West Riding towards Bradford. The line surveyed, from Royston to Bradford via Thornhill and the Spen Valley, would cut the distance from London to Bradford by 11¼ miles and from London to Scotland by 5¾ miles. Events moved quickly and on 25 July the same year the Midland secured its Act for the West Riding Lines, from Royston to Bradford (Fig. 3).

The line was to be in two sections, the first, just over 8¼ miles long, ending at Thornhill, and the second, eleven miles long, running from Thornhill to Bradford to terminate in a junction with the Leeds & Bradford Railway. The estimated cost of the work, which included the diversion or stopping-up of numerous public roads and the building of several bridges and tunnels, was £2,100,000. Among the many clauses protecting local authorities, private companies and neighbouring railways, may be mentioned H.W. Ripley's Trustees as to water rights at Bowling Dyeworks; securing John Leeming, North Holme Mills, against mishap in the diversion of Bradford Beck; and insuring the Great Northern Railway against subsidence of its short tunnel under Ripley Terrace, below which would be the Midland's long tunnel.

Construction of the West Riding Lines started at Royston Junction on 3 July 1905 and by 1 March 1906 they were open as far as Savile Town yard, Dewsbury, at the end of a short branch from Headfield Road. There was also a connecting spur to the Lancashire & Yorkshire line at Thornhill. This section contained several engineering features worthy of note, particularly a viaduct of twenty-four arches across the Blacker Beck valley and another of seventeen arches near Horbury Bridge. Near Thornhill a three-span bridge crossed the Calder & Hebble Navigation and at Headfield Road there was a substantial lattice girder bridge. An embankment was built from Headfield Road to Savile Road, at which point construction of the West Riding Lines ceased, pending modifications by the Midland Board.

Among the works never started were:

- A long viaduct across the Calder Valley at Dewsbury and a tunnel under Dewsbury Moor leading into the Spen Valley.

- A bridge across the London & North Western's New Leeds Line.

- A tunnel some 5000 yards long under Bierley Top, Bowling Park, Ripleyville and Broomfields, running into a covered way under Forster Square and below the existing Midland Station to main line underground platforms. The tunnel was to emerge 150 yards north of the platform ends and the line was to continue to Manningham Junction, just south of Queen's Road Bridge (Fig. 3).

In February 1905 the Midland shareholders were told that it had not been possible to proceed further with the West Riding Lines. Two months later a deputation from the City Council to Derby learned that diminished returns and serious engineering difficulties in Bradford had led the Midland Board to consider modifications to the authorized plan. The deputation gained the impression that there was a marked reluctance to undertake further work on the lines towards Bradford.

On 19 November 1906 the Yorkshire Observer gave an interesting outline history of the project to date and said that three courses were open to the Midland Board: to proceed with the construction; to obtain extension of time, or to abandon completion of the lines. Abandonment would be a staggering blow to the great industrial city of Bradford, because property in the central area had lain derelict for ten years, waiting for the upheaval to take place, and the result was 'a paralysis of the natural course of building development'.

Completion of the Connecting Lines at Thornhill had opened the way for passenger trains between Royston Junction and Midland Junction, but not quite as the Midland Board had planned. A service of three expresses daily between Bradford Exchange and London St. Pancras started on 1 July 1909, hauled by Lancashire & Yorkshire engines between Bradford and Sheffield, the only intermediate stop. This service foreshadowed the running of ' The Yorkshireman' over the same route by the London, Midland & Scottish Railway from March 1925 to late in 1939.

The modifications to the West Riding Lines, which the Midland had been considering, now began to take shape as the Bradford Through Lines Bill. Here the covered way and underground station gave place to a viaduct and high-level platforms 25 feet or so above the Midland Station, a radical change which meant that the line over Forster Square would be about 47 feet higher than the tracks planned to run beneath it.

The lines of the Lancashire & Yorkshire were now to be used between Thornhill and Oakenshaw, where ajunction at the latter was to give access to the Midland line through Bradford. Just over a mile from the Oakenshaw Junction was the southern entrance of what was to be a dead-straight tunnel 3600 yards long, under Bierley Top and Bowling Park, terminating in Ripleyville. From here the alignment was to continue as far as Fairfax Street, where a second short tunnel under Broomfields and Wakefield Road was planned, and this was to lead into a short cutting on the north side of Diamond Street, from which the city centre viaduct was to start.

From Broom Street to Leeds Road the lines curved round to avoid the Exchange Station. The four roads to be retained as thoroughfares in the central area were meant to be crossed by girder bridges, all of with a headroom of 15 feet, except at Leeds Road, where it was increased to take a double-decker tramcar. From Leeds Road to the forecourt of the Midland Station the viaduct was to carry the lines at a height of 25 feet above Forster Square. The lines, continuing above platforms 5 & 6 in the station below, wisely veered slightly to the right to avoid Trafalgar Brewery, and went on to a junction with the Leeds & Bradford formation at Queen's Road Bridge. The cost of the modified Through Lines was £815,667.

During the course of a debate in October 1910 the City Council offered a rates rebate of £8000 to the Midland as an inducement to proceed with construction. Another inducement was a guarantee to make good Ripley's water supply from the Corporation reservoirs if the Dyeworks' own supply happened to be intercepted by the tunnel - at an estimated cost of £5000 a year if the guarantee had to be implemented. On the day of the debate, 25 October, the Yorkshire Observer, reporting on the proceedings, said that £8000 per annum for 20 years was the equivalent of a 1½d. rate, and a big price to pay for the 'enormity' of an overhead railway. In the Council Chamber concern was also expressed as to how much the new railway would be used if the Midland continued to route most of its traffic via Leeds. Alderman Hayhurst pressed for a clause compelling Anglo-Scottish expresses to stop at Bradford, otherwise what would be the use of through lines?

On 19 November 1910 a Bill entitled 'Midland Railway (Bradford Through Lines)' was deposited and soon afterwards the Midland Board conveyed its plans - the modified West Riding Lines - to the Town Clerk of Bradford.

Great was the chagrin of Dewsbury Corporation, which had set so much store on the West Riding Lines, by which it hoped to get north and south outlets on a main line railway. Doubtless civic pride had been aroused at the prospect of the Midland's prestigious Anglo-Scottish expresses calling even briefly at Headfield Road Station, and the Council expressed its annoyance by opposing the Through Lines Bill, on the legitimate grounds that the Spen Valley line was already choc-a-bloc with traffic. Dewsbury considered it difficult if not impossible to absorb Midland trains punctually over so crowded a line, but the opposition was of no avail. On 25 July 1911 the Bradford Through Lines Act received the Royal Assent.

With an abundance of good building stone on its Bradford doorstep the Midland might reasonably have been expected to grace the city with a masonry viaduct, but this could not be taken for granted. A local architect, James Ledingham, warned that the railway might simply construct a viaduct of blue bricks, with girder bridges over the streets. In support of this he cited the North Eastern Railway's approach to Leeds New Station over a long brick viaduct built some forty years before.

Ledingham advocated the laying-out of a new thoroughfare in Bradford, with a road 18/20 yards wide before the viaduct and one 8/10 yards behind it, whichever the front and rear might be. The viaduct itself could be architecturally treated, with offices and shops in the arches: the buildings flanking the roads might be as much as 110 feet high, and the same width between them. Perhaps the reverse curvature of the viaduct would have lent itself to the treatment suggested, with an arch or two left open for access.

In 1918 the Midland Board gave Bradford Corporation a categorical assurance of its intention to complete the Through Lines, but the writing was on the wall. Post-war inflation; diminishing profits; the pre-eminence of Leeds, which made any plan to by-pass it unthinkable; and the successful widenings of the main line between Skipton and Leeds, were developments which put paid to any hope of railways through Bradford.

As late as 1914 the Midland had purchased Waller's Brewery lying between the passenger and goods lines in Bradford at the bottom of Trafalgar Street. The clearing of this site would eliminate the kink where the line had been meant to pass east of the brewery buildings.

On 18 November 1919 the Midland formally abandoned the Bradford Through Lines plan, and on 30 September 1920 all the property in the central area which had been acquired for demolition was sold to Bradford Corporation for £295,000.

Conclusion

Exactly what difference the lack of a through railway line has made to Bradford is too big a question to be attempted here, but its unusual position - 'the town built in a hole' - did not prevent Bradford from becoming the wool capital of the world. History is governed by geography, and the difficulty of getting tracks across a town centre crowded into the narrow valley of the beck threatened all the schemes.

The best time to construct the proposed line was almost certainly in 1846, before the new Bradford, the prosperous Victorian town with its impressive stone buildings, had begun to take shape. After this there were plenty of reasons for doing nothing, as in 1847 for example, when George Hudson fell from grace and thousands of small investors were ruined. As years went by commercial interests, like the protection of Ripley's water rights, assumed greater importance, and fierce rivalry between competing railways hampered progress.

There is some doubt how great the 'Great Depression' was in Bradford, but a period of good trade ended in 1875, after which there was little talk about prosperity until the end of the century. This was clearly no time to be embarking upon costly speculative ventures, although in 1888 the new Exchange Station became fully operational, with five platforms each for the Great Northern and Lancashire & Yorkshire Railways. In 1911, when the Through Lines Act received the Royal Assent, success seemed assured, but the Great War dashed all hopes. Thoughts may then have turned to the warning uttered by the Yorkshire Observer on 19 November 1906:

"Bradford is today on a siding and there, if this scheme is allowed to lapse, it may remain till the crack of doom."

Without looking quite so far ahead, we know that Bradford, of all the large provincial centres - Birmingham, Leeds, Leicester, Manchester, Nottingham and Sheffield, for example - is still the only one deprived of through trains. The Exchange Station no longer exists, and the Midland Station provides only a few local services. One by one the large goods yards, which used to handle huge consignments, especially of wool, have closed down too. Yet far reaching alterations to the city centre, coupled with a need to meet the rapidly changing demands of passenger transport, have given Bradford a modern interchange, shared by trains, local buses and long-distance coaches. But with only four railway platforms this is not quite the kind of central station 19th century planners had in mind, and for those who arrive in Bradford by train it is still' All change'.

Notes

1. The Bill also asked for authorization of a branch from Whitehall Road in Wortley (hence Whitehall Junction) to the North Midland at Hunslet, and for an east-to-south curve from Leeds Junction outside the Wellington Station to give through running towards Sheffield over the Hunslet branch. (back)

2. On the same day the Manchester company opened a short branch from Greetland, where the junction faced Normanton, to a station at Shaw Syke on the fringe of Halifax. (back)

3. The capital for the new venture was to be equally subscribed by the principal and subsidiary railways, providing 25% each, and the railway was to be managed by a committee of equal numbers from each of the four constituents. (back)

4. In 1845 the thoroughfare we know as Well Street was named Leeds Road, being a short branch of the Leeds & Halifax Turnpike Road. Well Street was a narrow, curving road, later to become the south side of Forster Square (really a triangle in plan), after demolition of the decayed property in Broadstones. (back)

5. The 'Short Line' to Leeds.

In June 1851 the Lancashire & Yorkshire obtained an Act for the abandonment of the unstarted railways inherited from the West Riding Union, whereupon the discontented Short Line party itself promoted a successful Bill for a line entitled the 'Leeds, Bradford & Halifax Junction Railway', which the Great Northern Railway had agreed to work. The line was absorbed by the Great Northern in 1865.

Running Powers enabled Lancashire & Yorkshire tracks to be used between Bowling and Halifax; and at the Leeds end the London & North Western Railway (ex-Leeds, Dewsbury & Manchester) afforded access to the Central Station from a junction at Wortley. This arrangement conveniently left only 7½ miles of new line to be built. A supplementary Act of 1853 enabled the construction of a mile-long branch from Laisterdyke down to a rather out-of-theway station at Adolphus Street in Bradford, opened on 1st June 1855; a day of fulfilment for the 'Short Liners'.

1864 saw the opening of a steeply graded line from Hammerton Street Junction, on the Bradford branch, to Mill Lane Junction on the Lancashire & Yorkshire, which gave the Great Northern access to an enlarged but still ramshackle Exchange Station. (back)

Sources

Leeds & Bradford Railway Act 1844 and Leeds & Bradford Connecting Lines Act 1846 in Bradford Acts of Parliament 1842-1849, Vol.5.

Midland Railway (West Riding Lines) Act 1898

Bradford Through Lines Act 1911

P.E. Baughan, North Of Leeds, 1966.

H. Hird, Bradford in History, 1968.

E.G. Barnes, The Midland Main Line, 1969.

J. Fieldhouse, Bradford, 1972.

D. Joy, South and West Yorkshire, 1975 (Vol.8, A Regional History Qf Railways).

O.S. Nock, Railway Archaeology, 1981.

© 1986, John Thornhill and The Bradford Antiquary