The Lost Villages of Baildon Moor

Joyce W Percy

(First published in 1999 in volume 7, pp. 19-46, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

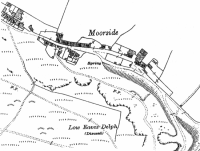

Figure 1.

To the north of Baildon Moor, where the steep ground and rough moorland vegetation merge into gentler green fields, lay the tiny villages of Moorside and Low Hill (Figure 1). There is no evidence to suggest when the first settlements occurred there, but land near Faweather Grange, about ¾ mile beyond Low Hill, belonged to Rievaulx Abbey and there are a number of stone flagged packhorse tracks nearby. A map of the Baildon commons by Robert Saxton in 1610 shows enclosures extending north and west from the site of Moorside and it is clear from a map of the enclosures of the moor farms belonging to Francis Thompson, the Lord of the Manor, in 1737 that there were farms on the side of the moor in the eighteenth century. However, no such farms were shown at Moorside or Low Hill. The Tithe Award of 1845 lists both arable and grass fields adjacent to Moorside.

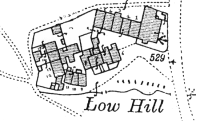

The village of Moorside lies immediately under the steep, quarried outcrop known as the Eaves, about ¾ mile from Baildon. The 23 cottages were originally known as The Row, a name which aptly describes their lay-out along the lower side of a narrow paved lane, with the moor rising steeply on the other side. At Low Hill, next to the Hawksworth road and about one mile from Baildon, there were fifteen cottages clustered together, as were the thirteen at Sconce, another hamlet about ½ mile beyond Low Hill.1

The villages were all built on or near the spring-line. There were three springs at Moorside of which one in particular, known as Mary Peel's well; provided excellent drinking water. Low Hill and Sconce obtained water from Crag Well, later known as Joe's Well, situated between the two. Water was piped to Low Hill from the stream flowing from the well. In this respect, the moor villages were much better served than Baildon itself. The water, flowing from sandstone, was soft and pure, while the springs in Baildon, though numerous, were hard and some were polluted by drainage and unfit for use.

Many Baildoners from the top of the village used to fetch water for drinking from the moor villages, while others bought water fetched by cart from the Acre Well higher up on the moor.

Immediately behind the houses of Moorside are the Low Eaves, quarried for sandstone, with a further quarry at High Eaves in the direction of Low Hill. With good building stone so accessible, all the cottages, like most others in the district were built entirely of stone, with stone-flagged floors, stone roofs, stone sinks and even stone stairs. The present church at Baildon was also built of stone quarried at the Eaves in 1847. A crane at Low Eaves Delph is shown on the 1893 Ordnance Survey map but the quarry was disused by 1934. Upright stones with holes once supporting handrails to guide the quarrymen can still be seen on the steep track above Moorside.

Coal is known to have been dug in the Baildon area as early as 1387, when John Vavasour, the Lord of the Manor, complained that several people had dug coal on the moor to the value of 100 shillings. Coal pits on the edge of the moor west of Low Hill are shown on Saxton's map of 1610, with a 'colepithowse' on or near the site of the village. Coal was extracted by various methods, open workings, day holes, which were horizontal shafts into rising ground, bell pits and from deep mines. Bell pits were sunk where the coal was not far below the surface. When the coal was reached the shaft was broadened out, so forming the shape of a bell. On both the 1737 map of the enclosures and the 1845 tithe map land across the Hawksworth road from Low Hill is named Colepit Close. The workings here, together with those dotted along the edge of the hill towards and beyond Sconce, below Acrehowe Hill and all over the lower slopes of Baildon Moor were all described as old coal pits on the 1852 Ordnance Survey map. The hollows left by these workings are vivid reminders of the extent of the mining. Although the coal dug from shallow pits was used for household fires it was not of good quality. The main use for coal from the 18" thick seam worked from shafts on the higher parts of the moor in the nineteenth century was in the newly installed steam engines in the mills, particularly at Baildon and Eldwick, though it was carted as far as Burley and Otley. Lobley Gate Pit, the last of the three; closed down in the late nineteenth century. Flooding made it unworkable and when the railway to Ilkley opened in 1876 better coal could be delivered more cheaply to Burley and Otley.

In supporting the purchase of Baildon Moor by Bradford Corporation in 1899, William Booth Woodhead, civil engineer and surveyor, stated that coal had been worked there until the last fifteen or twenty years but he believed there was no coal left of commercial value.

It is widely believed that the cottages at Low Hill, Sconce and Moorside were built for miners in the eighteenth century. When the outcrops along the northern edge of the moor were being worked extensively the villages, with their good water supplies and building stone, were clearly very suitable sites. It seems probable that there were already farms or small holdings there and the earliest references to Moorside date from the mid-eighteenth century, though it must be remembered that Moorside village was commonly called Rowand the term Moorside was also used for the area.. Two members of the Baildon Methodist Society lived there in 1763. Jenny Milner, born in 1742 (and after whom Jenny Lane in Baildon is named) lived in Moorside for a time after her wedding, and William Newall, a clogger, died there in 1779. In 1807, Joshua Briggs who had previously opened a Sunday school at Eldwick, moved to Moorside, where he again had a school before moving to Tong Park and then to Baildon village. A descendant of the Thomas Atkinson who built two cottages at Low Hill in the late 1830's used to hear from his grandfather and great uncle that Low Hill was built for miners.2 The Land Tax records for 1781 include an entry for the late Mr Meyer, Esq. the Lord of the Manor, for coal mines in Baildon and it is tempting to think that the cottages were built for the mine workers on the edge of the common land. However, when the census was taken in 1841, the first to give such information, there were only two miners in Low Hill and three in Moorside.

The building style of the cottages was typical of workers' housing in the area in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but the earlier ones cannot be accurately dated. The smaller of the two Moorside farms at the west end of the village, may have been the earliest. It was inherited by John Walker on the death of John Walker of Hope Hill, Baildon, sometime between 1807 and 1809. The farmhouse and five closes, then in the occupation of Thomas Walker, together with two cottages, one used as an outhouse, and gardens were conveyed to Michael Walker of Baildon, farmer in 1838 (Figure 2). The total acreage was 6a 3r 9p. By a separate deed of the same date, Thomas Walker bought the four cottages adjoining the farm and erected by John Walker, deceased, 'many years ago', on vacant ground inherited by him, and therefore prior to 1809. In 1890 when the farm was sold to the Denby family of Tong Park, manufacturers, it was referred to as Moorside Farm, although in more recent times the other farm was known by that name. It was sold again in 1920, together with the adjacent cottage, farm buildings, stable, poultry house, croft and garden, then known as 4 and 5 Moorside (Figures 3 and 4).

Three other cottages at Moorside (numbers 9. 10 and 11) presumably dating from the eighteenth century were sold by John Silson of Baildon, cloth maker, to John Naylor of Hawks worth, butcher. In 1855 they were described as 'anciently erected' and the northernmost one was untenantable. Adjoining them were now six further cottages and a shop erected by the late John Naylor on part of the ground belonging to the three ancient cottages. All nine, together with two more, and 'old' cottage, once Richard Mawson's outbuilding, coal houses and gardens all on the opposite side of the road, and 'situated and adjoining upon Baildon Moor' were sold by William Midgley, coal owner (who worked the three mines on Baildon Moor) to Joseph Copley of Baildon in 1878. He also purchased the adjoining house, known as Mawson House, and the shop and garden formerly occupied by Richard Mawson, a plasterer who lived there for many years (Figures 5 and 6).

Four other cottages with gardens, waste ground and work premises also said to be at Moorside, but almost certainly at Low Hill, were sold in 1803 to Stephen Atkinson, carpenter, by Faithy Hill and Thomas Hill. The Court Rolls for 1806 confirm that since the last court held in 1799, Stephen Atkinson had purchased four 'cottage houses' from Thomas Hill and three more from William Wheelhouse, for which he had paid fealty of 1s4d to the Lord of the Manor. Stephen Atkinson died between 1820 and 1824, devising eleven cottages to his wife, Ann, who in turn devised her estate to her children, Stephen, Thomas and Martha Atkinson, and Peter Homer and Jeremiah Booth.

As at Moorside, deeds provide evidence of earlier farm buildings at Low Hill. In 1836 a fold yard was shared between three people. and Stephen Atkinson, carpenter, used an old house bam in the fold yard as a wood house, and the parlour of the adjacent cottage as a workshop. Small buildings behind two of the cottages were called 'Milkhouse'. Thirteen cottages and their occupiers were included in the deed, nearly all having gardens and pig cotes. One pig cote adjoined Stephen Atkinson's workshop and another the kitchen(!) at the back of the house occupied by Jeremiah Booth, Martha Atkinson and Thomas Atkinson. There was a shared croft next to the house bam and a building in the comer of a garden used by five of the occupiers as a wool wash house. They also shared a privy to which there was right of access across the fold yard. Occupiers of three cottages and the milkhouse had the right to enter ground at the west end of the premises and place ladders for repairing them. By 1840 two further cottages had been newly erected by Thomas Atkinson, weaver, since deceased, on the site of a cottage lately occupied by Jonathan Holmes. The one on the south-west was occupied by Abraham Reynard together with the ancient part of the said cottage and the right of ladder room for its repair. There was a garden on vacant ground in front of the new cottage and a new pigcote. The westernmost part of the croft was now walled off and used as a garden by the occupier, subject to the right of access for the repair of Martha Atkinson's cottage.3 The direction and gardens suggest that these cottages were the larger ones later numbered 6 and 7. Number 7 is shown on the map as adjoining and partly encroaching on number 8 on the west. In 1912, four of the cottages, numbers 9, 10, 11, and 15 were mortgaged by Sarah Ann Denby of Faweather to Ellen Exley and Hannah Exley, spinsters, of Menston. (Figures 7, 8 and 9)

The Court Rolls of the Manor of Baildon reveal that a Stephen Atkinson had purchased three cottage houses from William Wheelhouse and four more from Thomas Hill (possibly in Low Hill) for which he paid fealty of 1s4d to the Lord of the Manor in 1806. When he died he devised eleven cottages to his wife, Ann Atkinson, who in turn devised her estate to her children, Stephen, Thomas and Martha Atkinson, Peter Homer and Jeremiah Booth.

Population in the nineteenth century

The census enumerators' returns which are available for every tenth year from 1841 to 1891 give a fascinating insight into the families who lived in Moorside and Low Hill. No such information was gathered in earlier years and later censuses will only be made available one hundred years after they were compiled. They list only those people who were present at each address on the census night, a Sunday usually in April. While Low Hill was always named as such or, more specifically, as Baildon Moor Low Hill in 1861, Moorside was described variously as Row in 1841, Moor in 1851, Baildon Moor Row in 1861 and Moorside thereafter. The houses were not numbered originally, and the enumerators did not necessarily list the houses in order.

In both villages the number of inhabited houses declined markedly over the fifty years covered by the censuses and by 1881 several pairs of houses were joined together. (Table 1) It is intriguing that the total of inhabited and uninhabited houses did not remain constant in either village. By the late nineteenth century, there were plenty of empty houses in Baildon as a whole and Moorside and Low Hill were obviously no exception. However, from about 1890 two Bradford doctors, Johnson and Dunlop, promoted Baildon as a healthy area in which to live. Many people moved out of Bradford, particularly when the golf club started, while others rented the moorland cottages as holiday homes. It is possible that some of the houses listed as uninhabited on census night 1891 were already holiday homes and unoccupied on that night. While many of the families remained in the villages for the decades covered by these censuses, there were a surprising number of changes of occupancy. Very many of the families only appeared in one census.

The number of inhabitants declined even more dramatically than the number of inhabited houses. From a total of 225 people in the two villages in 1841, there were only 94 fifty years later. Likewise, the average number of people per house decreased from nearly six in 1841 to 3.8 in 1891. In addition to large numbers of children in the middle years of the century, there is considerable evidence of extended families, with an elderly parent, widowed sister, married son or daughter, niece, nephew, or grandchild in many of the families, but remarkably few elderly people. In 1851, for example, there were only three men and one woman aged over 65 at Moorside and just one, Richard Paley aged 89, at Low Hill. The great majority of the inhabitants were born in Yorkshire and in what is now the Bradford Metropolitan District, but in 1851 three had come from Norfolk, formerly the centre of the worsted industry, two from Bury St. Edmunds, two from County Durham, one from Liverpool and three from Ireland. There were also fourteen lodgers in the two villages in 1851, but none in 1891, presumably an indication not only of the greater availability of property but more particularly of increasing prosperity, more people being able to afford a home, and fewer so poor that they needed lodgers to eke out poverty wages in spite of serious overcrowding.

Even before Forster's Education Act of 1870 caused Local School Boards to provide education for all children between the ages of five and thirteen, some children at Low Hill and Moorside were classed as scholars, two in 1851 and six in 1861. A school was held at Moorside by a Mr. Robinson in the cellars of the first three cottages at the west end. The Wesleyan Methodist Sunday School, built in Baildon in 1815, was for a time attended by all denominations and also used as a day school. In 1849, a Church of England school opened in Baildon and a Moravian school about the same time. By 1871, the number of scholars aged five to thirteen in the two moorland villages had already increased to sixteen, with two four year olds and one three year old also listed. In the following census there were twenty-five children at school, before the numbers declined to nine in 1891. By no means all the eligible children attended school.

Occupations of the Villagers

The cottages at Moorside and Low Hill may have been built for miners and stone workers, but it is clear from the census returns of 1841 to 1891 that the majority were by then occupied instead by textile workers (Table 2). However, the censuses can only indicate the main employment and it is likely that many of those working from home as wool combers or weavers would also take casual work as miners, quarriers or labourers, as well as tending their gardens and pigs. In 1841, Moorside had only three miners, young brothers aged thirteen, eleven and nine, and Low Hill two brothers, aged fifteen and thirteen. Interestingly, their fathers, John Greenwood and William Robinson were both described as agricultural labourers and so the boys would have been unable to take part in the family occupation of weaving or wool combing as happened in so many of the families. Ten years later, in 1851, there were no miners in either village, but by 1861, the number had increased to twelve, seven at Moorside and five at Low Hill. In contrast to 1841, most were adult men. One had a son aged twelve who was also a miner and there were three miners aged fourteen, fifteen and seventeen described as boarders or lodgers where the head of the household was also a miner. The pattern for Moorside was much the same in 1871, a total of eight, two of whom were sons aged twelve and thirteen, one a 'putter' and the other a 'huryer'4. By 1881 there were only three miners at Moorside and none thereafter, while at Low Hill coal mining as an occupation had already died out completely. Lobley Gate Pit, the last of the three to remain open, closed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Stone workers, while more diversified than coal miners, being variously described as quarryman, stone miner, delver, stone dresser and stone waller, as well as stone carrier (quarry) and labourer for masons, were no more numerous in the period of the available censuses. There were none in 1841 and only two in 1851, both at Low Hill. One, a married man aged 46, and his wife lodged with the other. Of the three in 1861, two stone quarriers lived at Moorside and a stone breaker at Low Hill. In 1871, a period of greater prosperity and more building, there were six stone workers at Moorside, three at Low Hill, and two engine 'tenters', both from outside the area. John Booth, aged 29, of Moorside was born at Holmflrth, and William Robinson, aged 28, of Low Hill was born at Bowling. It seems likely that he had worked at the Bowling Iron Works. By 1881, numbers of stone workers had increased to nine at Moorside and four at Low Hill, before declining to only two. The entry for William Robinson in 1881, originally 'engine tenter, stone' was amended to 'driver' by the enumerator.

In sharp contrast to these low numbers of both miners and stone workers in the two villages by the mid-nineteenth century, were the textile workers, mainly weavers and wool combers. Comparisons over the five decades are difficult because categories and the information given vary, but it is nevertheless very clear that most of the families were involved in some way in the production of cloth, mainly worsted. There was a very marked change in the type of work, with a transition from home-working, both wool combing and hand loom weaving, to factory work, before this too declined. In 1841 trade was much reduced and the cost of food so great because of the Com Laws and protective duties, that many suffered extreme poverty. Both wool combing and weaving were poorly paid. Wages in 1852 were 8s a week for handloom weavers, 9s for power loom weavers, 10s for wool combers and 14s or 15s for sorters. Women earned about 8s, children working full time 4s and those on halftime 2s. In the two villages in 1841 there were 33 wool combers, including seven wives, but by 1851 with a general improvement in trade the number had increased to 52, eleven of them wives. Possibly because of competition from woolcombing machinery, only two children were employed as wool combers in 1841 and in 1851 there was just one. By the 1860s handcombing was really out of date. Only eight handcombers were left in 1861, all at Moorside, and there were none in the next two censuses. Five of the eight were aged over 50; one was 73 and Thomas Fawcett aged 83 was listed as a wool comber receiving parish relief. It is not clear whether he was retired or not. When three woolcombers, aged eighteen and sixteen, appeared in 1891, it seems reasonable to assume that they were working in a factory.

Even more numerous than the wool combers were the weavers, there being 61 'stuff weavers', that is weavers of worsted, including sixteen wives, in 1841. No distinction was made between handloom and powerloom weavers at that date and it seems likely that they were all handloom weavers working at home. This is perhaps borne out by the fact that whole families were employed in the same trade, excluding only the youngest children. In one family, James Rennard, his wife and all six children, including a girl of ten and a boy of seven, were stuff weavers. Joseph Rennard and William Rennard, presumably all related, and their wives and children aged fourteen and fifteen (but not those aged six, ten and twelve) were also stuff weavers at Moorside. From 1851, weavers were divided into handloom and powerloom weavers, and according to whether they wove worsted or woollen cloth. There were only nine handloom weavers in 1851, with two weaving tweed in 1871 and none thereafter. The number of power loom (worsted) weavers, in contrast, increased from sixteen in 1851 to 31 in 1861, before declining to nineteen, twenty-two and three in the next three decades. The nearest mill to the villages was Low Millon the present caravan site on Hawksworth Lane. It was a long, low building without much headroom, and had both a water wheel and a steam engine. When it burned down for the third time in 1881 it was not rebuilt, which no doubt accounts for the decline in the number of weavers by 1891. There were in addition a few powerloom (woollen) weavers, but only a maximum of seven in 1851 and none in 1891.

In 1841, 25 'Factory' workers were under twenty years of age, the two youngest being nine and all but two lived at Low Hill. The type of work was not specified- but from 1851, most of these young factory workers were described as spinners. There were only nine by 1851, five of them aged under thirteen of whom the youngest, Elizabeth Greenwood, was only seven. However, her mother Martha Greenwood, a widow aged 40, was described as a pauper, even though all five of her children were working, an indication of the very low wages earned by children. The number of spinners gradually increased to eleven in 1861, fifteen in 1871, and sixteen in 1881, before declining to only seven in 1891. By this date, they were presumably working at other mills in Baildon.

After 1871, the specific occupations of the textile workers became more varied. There were, for instance, six warp dressers in 1871, four in 1881 and two in 1891, some of them working in cotton. Other workers were a burler, drawer, piecer, reeler, twister, rover and bobbin winder, but were very few in number. Most worked in worsted, but a few in woollens.

Agricultural labourers, varying in numbers from only one in 1851 to a maximum of six in 1871, found employment at the two small farms at Moorside, and possibly elsewhere. Intriguingly, the acreage of the farms, which is not given for 1841 or 1891, varies for each of the other censuses. One can only assume that Thomas Denby, who farmed 36 acres in 1851, held some land elsewhere or sold only fifteen acres to Joseph Woodhead by 1861. Benjamin Hutton, a widower aged 76, farmed twelve acres in 1871 when his son-in-law, James Royston of the same address, gave his occupation as agricultural labourer. Ten years later, James Royston farmed the twelve acres. The other smaller farm, belonging to the Walker family, was said to have either six or more usually seven acres.

Small numbers of people in the two villages, usually only one or two in each census, were employed in a variety of trades and most appeared in only one or two censuses. These included a bread baker, grocer and green grocer, broom maker and his wife, coal dealer, shuttlemaker, reed maker and a gamekeeper. In 1841 there was one apprentice shoemaker and ten years later a family of four cloggers and pattern makers, presumably father and three sons, all lodging with Thomas Denby, farmer. Richard Mawson was listed as a plasterer aged 35 in 1841 and appeared again in each census, [mally being described as a retired plasterer aged 76 in 1881. Another plasterer, Lewis Copley, had taken his place. Stephen Atkinson, a joiner or carpenter of Low Hill, likewise appeared in each census from 1841 to 1881, by which time he, too, was retired and aged 76.

The extent to which women were employed cannot be accurately deduced from the census returns. In 1841 relationships were not stated, so one cannot distinguish wives from other female relatives with any certainty. The family was usually regarded as an economic unit and the same occupations were ascribed to the women as to the men. A few were listed as agricultural labourers and in one case a joiner. In only a few instances was the column for occupation left blank, despite the instruction that 'the profession etc. of wives, or of sons and daughters living with and assisting their parents but not apprenticed or receiving wages, need not be inserted.' As a result we probably have a truer indication of the extent to which wives and children in Moorside and Low Hill were employed, at least partially, in 1841. From 1851 to 1881, it was specifically instructed that 'the occupations of women who are regularly employed from home, or at home, in any but domestic duties [are] to be distinctly recorded' and in 1891, the occupations of women and children, if any, were to be recorded. Eighteen wives were employed in 1851, four of them in a different occupation from their husbands, and only seven were not employed. The position had changed completely by 1891 when sixteen were not employed and only one was in employment as a worsted weaver. Of the other women, widows, sisters, and mothers-in-law, approximately three each year were classed as a female servant, housekeeper or charwoman. There was one nurse in 1851 and usually two or three dressmakers lbonnet makers. Also in 1851, two widows and an 89 year old male woolcomber were paupers. The entry for another widow, Hannah Midgley of Low Hill, probably 'retired weaver', was over-written with what seems to be 'W H xis. 6[d] cash'. The letters W H may mean the workhouse and that outdoor relief of 11s 6d was paid in outdoor relief. Ten years later, Thomas Fawcett, a widower aged 83, was described as a 'wool comber (Parish Relief)'.

By the last census available, 1891, when the two villages were clearly in decline, there was a marked change in occupations. Not only had mining and quarrying practically ceased, but fewer textile workers remained in the villages after the closure of Low Mill. Occupations not previously recorded include a butcher, a night watchman, a com miller, three men living on their own means, and a retired policeman.

Life in the Moorland Villages

While by modem standards, those cottages occupied by the larger families and used for weaving and woolcombing would have seemed very overcrowded, they had quite a large living area, were two-storeyed and sturdily built. Compared to the insanitary back-to-back housing, courtyards and cellar dwellings of Bradford, or the tiered houses in the steep streets of Baildon, they were desirable homes and remained so for nearly two centuries. The report on the township of Baildon to the General Board of Health in 1852, stated that because of the availability of good sandstone a cottage letting for £3 10s [per year] could be built for about £40. In parts of Baildon itself

houses will be two or three stories high on one side, and only one story high on the other. I should think not one tenth of the people live in floors one above another and where several families live under the same roof their houses form distinct tenements.

Such houses had no staircases or internal passages but the steepness of the ground enabled each floor to have a separate entrance. Most of the Baildon village wells were polluted, and the water hard and ferruginous. As a result goitre was common. The hardness of the water at the town wash-house belonging to the Lord of the Manor also meant that fewer pieces could be washed and therefore less money earned. At the town cross 'the stream was unfit for anything but liquid manure; the stench was intolerable, and the steps covered with human ordure.' There was only about one privy to every 25 houses, said to be comparable only to Bacup. In comparison, the villages of Moorside and Low Hill enjoyed plentiful pure, soft water, for drinking and for washing wool, privies shared between only two to five cottages and fresh air from the moor. In describing the moor, the compiler of the report concluded, 'I do not think I have visited any place combining physical circumstances more favourable to health and longevity.' It would be interesting to know the extent to which the moor villagers enjoyed better health than those of Baildon itself. James Steele, surgeon, the only medical practitioner in Baildon, reported to the enquiry that fever in the township was very common and also diseases of the chest. The fever would usually last two or three weeks, five or six if it became typhus fever. It affected all classes but some operatives had to return to work before they were fit. There was scarlet fever in the town at that time and frequently dysentery. In 1826 and again about twelve months before the report there were epidemics of typhus fever which he attributed to want of cleanliness and want of pure water. The latter one raged for about a month and there was no medical relief provided by the parish. There were sick societies in Baildon but they had no medical officer.

The figures supplied by Mr. W. Holmes the district registrar showed that the population in the township had decreased in the past ten years, mortality rates having increased there as in nearly all other places visited. In 1851 the death rate, despite some improvement, was still 20.21 to 1.000, which was about 25% higher than in 1841. Infant mortality was at least double what it ought to have been, and only a quarter of those born in Baildon would survive to maturity.

Giving evidence on the social and moral condition of the inhabitants of Baildon, the Rev. J Mitton stated that a large majority of the people did not attend any place of worship. Gambling was probably still a prevalent vice among young men. Illegitimate births were 'greatly beyond the average of places, and open adultery is a very prevalent sin here…In the streets the necessities of nature are obeyed, and that even by adults.'

As a result of the enquiry, the Public Health Act of 1848 was applied to Baildon. Three reservoirs were built on the moor, the first in about 1856 and the others in 1876/7 and 1891. However, the moor villages were not connected to the supply and therefore did not pay the water rate.

In the nineteenth century, most of the cottages were not only the homes but also the place of work of the occupiers. A typical cottage consisted of a large living room with a fireplace and a kitchen or scullery. Stones stairs led up to a bedroom large enough for two double beds. A few of the cottages were rather larger. Furniture would have been very sparse and similar to that in the Bradford houses described by William Cudworth, - a deal table, hard-bottomed chairs, a cradle, a chest containing malt or meal and a bread-creel hanging from the ceiling and containing oatbread or havercake. A chest of drawers or a clock would be a luxury. There might also be 'a shut-up bed' with a flock mattress arid blankets for the parents in the living room, as well as a further bed, possibly with a chaff mattress, for the children upstairs. In a weaver's cottage, the upper room might have one or two looms and be used as a bedroom at night. Hand combers used either the living room or bedroom as their workshop. In the middle was a pad-post, a stout pole into which was screwed an iron fitting called a 'pad' and the heated comb was fixed onto this. A handful of wool heated with hot oil was hung on the teeth of the comb and drawn out with another heated comb. The charcoal stove for heating the oil and combs filled the room with noxious fumes. A woolcomber's cottage could be recognised by the blackness of the ceiling and Bradford woolcombers were described as 'pale and cadaverous, few reaching fifty years of age.' The combers in the moor villages would usually receive their wool and oil from Low Mill in Hawksworth Lane and deliver the finished 'tops' there on a Saturday afternoon. All members of the family would help, the youngest making up handfuls of wool ready to be thrown on the comb.

Diets were very simple, oatmeal, potatoes, bacon, milk and treacle being the staple ingredients. Breakfast was usually porridge, possibly with blue milk, dinner might be potatoes and bacon if available and supper porridge again or oatcakes. Only on a Sunday was there likely to be any meat. It was cooked together with potatoes and onions and the dish placed on the table for the family to help themselves. Meals gradually became more varied with a general improvement in economic conditions. The main meal might be a sheep's head broth with dumplings, rabbit stew, or potatoes and vegetables. When cast-iron cooking ranges were added, it became possible to bake in the oven instead of boiling everything in a cast iron pot or making oatcakes on the bakestone. Sunday meals became more varied, with a Yorkshire or seasoned pudding with gravy and meat, and possibly cold meats, bread and cake at tea-time.

The cottages became more comfortable as work moved out to the factories and with reduced working hours, more time was available for leisure activities. A thriving social life developed at the Primitive Methodist chapel built at Low Hill in 1874. Primitive Methodism had started about 1810 when some Wesleyans felt that their church had lost enthusiasm for evangelistic preaching. Hymn singing, a strict moral code and temperance were the other main features. The first chapel had opened on the Bank Side in Baildon in 1824 and was replaced by the larger Zion chapel in 1865. Camp meetings were held annually on the moor, a fortnight before Baildon Feast, in an attempt to counter the drunkenness and licence that regularly occurred at that time. According to La Page, the Primitives also had a small chapel at Moorside for a time before building that at Low Hill beside the road to Hawksworth (Figure 10). It was built on land sold to Joseph Batley and twelve other trustees for £10 by the Lord of the Manor, Abraham Maud of Rylstone (Figure 10). The chapel cost £500 to build, for which a mortgage was taken out and events such as a public tea and humorous lecture were held to reduce the debt. Joseph Batley, a distinctive figure in his frock coat and top hat, who had a farm near Sconce, was a great advocate of temperance, giving rise to the name Joe's Well for the properly called Crag Well.

The chapel was well-supported by the two villages in its heyday and the register of baptisms shows that it was attended by people from Low Springs, Hawksworth, Sconce, Faweather Grange, Tong Park. and even Baildon itself. Chapel minutes record the purchase of a new set of china, 'six dozen in number', with a stamp to be chosen by four lady members, the appointment of trustees, a librarian and a magazine agent, and the purchase of a new harmonium. Anniversary services and Harvest Festivals were held in the open air and were a great attraction. In 1902 there was a musical service given by the Shipley Primitive Methodist choir in the afternoon, followed by a sermon and solos in the evening and the annual tea the next day, a Monday. Special anthems were sung by the choir, assisted by friends from other societies and 'an efficient string band'.

On 5 August 1902, a special concert, widely advertised with humorous posters, was given in the chapel by the Baildon Brigands, 'the notorious band who haunt in summer different recesses between the bounds of Baildon Moor and Rombalds Moor'. The chief of the Brigands for several years, 'Robert Scott Esq. etc. late of Nanny Goats' Rest but now of the Charming Residence known as "Hencote View", The Row,' had been induced to accept the office of Mayor of Moorside for the year. He was escorted from Baildon station, where their 'picturesque procession' created quite a stir. The programme included classical and humorous items, The Moorish Maid, Il Trovatore, Pinkerton's Purple Pills and When Father Laid the Carpet on the Stairs. Musical items were provided by the piccolo, mandolin and banjo and Prof. Feather was the ventriloquist. Refreshments were served to the Brigands, 'Joe's Well on this occasion being open all night.' Admission charges were 3½d, 6½d and 11½d and the school was crowded. After the concert the Brigands marched in procession back to Baildon village, performing in the Fountain Square, Town Gate and down Browgate till after midnight, their performance much appreciated, according to the Shipley Times, by the villagers and summer visitors to Low Hill as well as by the prominent residents and trustees of the chapel. The sum of £10 15s Od was raised and used for cleaning, painting and renovating the chapel, after replacing all the schoolroom windows, re-using as much of the old glass as possible.

The following year, 1903, a 'proper box ventilator' was put in, and new cocoa matting, carpeting, cushion covers and curtains for the rostrum, curtains for each doorway and a new lamp were purchased. The fourteen pews were to be covered with 'listcurl seating, 13½" wide' and thhe re-opening of the chapel to which the Baildon Primitives and Idle Primitives were invited, was celebrated on two successive Sundays, with tea provided for the choir. Many other events took place on Baildon Moor, which the people of Low Hill and Moorside no doubt participated in or enjoyed watching. From the early nineteenth century, it was the custom on Saturday afternoons for sports such as knurr and spell, arrow throwing and bowling with stones to take place on the moor. Baildon brass band often practised out of doors in summer at the junction of the Hawksworth and Bingley roads where there were a number of seats, and bands performed on the moor on the Sunday of Baildon Feast. Prizefighting with bare knuckles, although illegal, took place on the slopes in earlier times, while gambling towards the top of Hope Hill continued into the 1920s. On the Saturday afternoon of Baildon Feast there were donkey, and sometimes horse, races on the moor, with roundabouts, sideshows, a greasy pole, a tightrope walker and melodramas such as 'Maria Martin or the Murder in the Red Barn' in Baildon. People flocked to the Feast from Shipley, Windhill and Saltaire, the mills being closed on the Monday and Tuesday.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the moor became an increasingly popular resort for people from the smoky towns nearby. With increasing prosperity and easier access provided by the railway to Baildon station which opened in 1876, people came in their thousands to enjoy the moorland air. In 1899, the moor was purchased for £7000 by the far-sighted Bradford Corporation from the Lord of the Manor, Colonel William Wade Maude ofRylstone near Skipton. In recommending its purchase for recreation, to preserve the common and prevent further quarrying, William Booth Woodhead, civil engineer and surveyor, stated that the moor was used on Good Friday, Easter and Whitsuntide by as many as 30,000 - 50,000 Bradfordians at the same time. The moors were so frequented by the public that their value for sheep pasturage had deteriorated to almost nil, and the golf club was contemplating discontinuing because of the crowds.

While there was now no coal left of any commercial value, there was a large area of unworked fire clay and ganister and sandstone was the most valuable mineral. The Lord of the Manor had refused permission to work it, being reluctant to spoil so beautiful a piece of scenery but his successors might not be so scrupulous.

As well as those who came for the day to Baildon Feast, to band concerts, to play golf at the club founded in 1891 or to stroll on the moors, others considered Baildon to be a health resort and came to stay. The Shipley Times estimated that in the third week of August 1902 there were 300 visitors to Baildon, staying a week or ten days. There were also visitors who spent the whole summer in the area and particularly at Moorside. Shortly before Easter 1910 it was reported that

"The cottages at Moorside and Low Hill are being put in hasty repair, for now is the time when the city paterfamilias', with his wife and family, comes out for a spring and summer sojourn into the country. Loads of furniture were early this week being carted over the Eaves to the selected houses of the visitors. And if more cottages were available greater would be the population which from spring time till late autumn adds to the total of the villagers. The country is tempting just now… "

Easter Monday was the busiest day of the holiday. Soon after 5 o'clock visitors on their way to the moors were knocking loudly at the door of one farmhouse in Moorside, asking for eggs or milk. Many thousands walked across the commons and golfers' games were disturbed by such large crowds. By late July, accommodation could not be found in 'the more secluded parts on the outer edge of the moorland,' but only in Baildon village itself. Many white tents were erected and the wooden chalets built along the hillside near Sconce were occupied.

As the population of the villages declined following the closure of Low Mill, and the holiday makers took a less active part in village life, attendances at the Primitive Methodist Chapel at Low Hill also fell. At the yearly Trustees' Meeting in 1917 it was stated

"That in our judgement the time has come for the closing of Baildon Moorside Chapel, as it is not now needed. Great changes have taken residents and their children as seen in other days have been replaced. Cottages are now rented as holiday homes by town dwellers who make only occasional use of them and give no support to the chapel and its services. The congregation has been reduced to an average of six persons and most of these living at a distance would find Baildon Chapel as convenient for them or more convenient. A visit to the homes around the chapel by the minister and one of the stewards to make doubly sure of the facts destroyed all hope of saving the cause."

The circuit meeting was asked to sanction the sale of the building. Bradford Central Hall considered using it as a children's holiday home but did not make an offer and it was sold to Mr. Thomas Robinson for £320, with the fixtures and furniture included. It was run as a tea-house with trestle tables for a time during the 1930s, with one comer curtained off as living quarters. In 1980, it was again offered for sale with planning consent for conversion to a six-bedroomed house, for £25,000. Mains electricity was installed and land to the west was available for a septic tank.

A few cottages may have continued to be let as holiday homes beyond the 1930s, but with the shortage of housing during and following the war, they were once again occupied by young couples and families. By the time they were demolished most of the families had lived there for years. Only one of the cottages at Low Hill was then a weekend cottage. Former residents speak of them as comfortable and roomy. Moorside had electricity by 1947, but water was still fetched from the wells. One former resident of Low Hill remembers that everything was made of stone including a stone sink and a walk-in pantry with stone banks - no food ever went off there. In one of the cottages was a little shop and a Mr. Halliday used to sell hardware, paraffin, wicks, pegs and clothes lines from his van. Milk was brought round from Low Springs and measured out from a chum. But fetching in all the water was a real chore, as was walking in the snow up to the school in Baildon.

Access to Moorside was something of a problem at all times. Even in dry weather, the extremely narr9w track was difficult for vehicles while the stone sets played havoc with their springs. In deep snow, corpses were said to have been brought out on sledges and milk was delivered in the same way. But the picturesque village seems to be remembered primarily for that and for the delightful views across fields and woods to Hawksworth beyond.

The Final Years

It is somewhat ironic that the water supply, a principal factor in the siting of the two villages, Low Hill and Moorside, should also have been the main reason they were condemned as unfit and demolished in the 1960s. The report of the Medical Officer of Health and Senior Public Health Inspectors for Baildon in 1958 stated that they remained unsewered and that the pail closets were emptied weekly, but all subsequent reports concentrated on the water supply. As early as June 1961 a total of 94 houses, in five separate areas of Baildon including Low Hill and Moorside, were declared by the Baildon Health Committee to be 'unfit for human habitation and are by reason of their bad arrangement or the narrowness or bad arrangement of the streets, dangerous or injurious to the health of the inhabitants.' The most satisfactory solution would be the demolition of all the buildings. Alternative accommodation could be provided in advance and the council had sufficient resources for the purpose.

Nineteen residents of Moorside, almost all the occupiers, wrote to the Council stating that if a true report had been presented the properties would not have been declared unfit for human habitation. Details of their petition appeared in the Shipley Times, 6 September 1961. They had enquired of the Council's intentions before purchasing their properties and invested their finances 'hoping to live and enjoy a quiet life in these lovely old-world cottages.' They asked why they could not peruse the report of the recent inspection and were prepared to pay part of the cost of bringing their properties up to the required standard. If the order were carried out it would bring them financial ruin. It was agreed that the residents should have an opportunity to object before decisive action was taken, but just one month later, both Low Hill and Moorside were declared a clearance area to be acquired by compulsory purchase. There is no further reference to the residents' concerns. The clearance scheme did not, however, proceed smoothly. Following objections and public enquiries, three properties at Low Hill were excluded from the clearance plans. Some of the councillors argued that the money intended for clearance would be better spent on helping owners to bring their houses up to standard with improvement grants. However, the Council had to implement Government policy for clearing unfit houses and selecting houses would have made an overall scheme impossible. Most of the cottages in Moorside and Low Hill were purchased individually by the Urban District Council in 1964. A cottage with a coal house and shared garden, wash house and earth closet was bought for only £23, while £40 was paid for the dwelling house, formerly known as 'Mawson House', together with a shop, garden and other ground.

Moorside Farm, numbers 23 and 24 Moorside, was not included in the Compulsory Purchase Order and received an improvement grant in 1962.

Even when the properties had been bought and the occupants re-housed, it was some time before they were demolished. Tenders for the clearance of Moorside were accepted in September 1964, but in the following June the contractors were unable to complete. In August, the Council agreed to pay £105 for demolition to be completed at Moorside and £120 for Low Hill. Of the Low Hill properties the old chapel did not properly come within a clearance order area under the housing Act and was not then in use. No. 15 was excluded because the property was fit, having a piped water supply from Joe's Well; numbers 12/13 and 14 Low Hill were considered unfit but were given the opportunity to be improved because they were in the same block of buildings as 15 Low Hill. The Council did not wish to purchase the houses and the owners were prepared to carry out the recommended improvements with the exception of installing a piped water supply from the Rombalds Water Board which would cost over £1,000. The solicitor for the owner of 14 Low Hill wrote of the 'illogical and ludicrous' situation in which one cottage had a piped water supply from the well but permission was refused for other owners to arrange a similar supply. Unless the Council could within two weeks quote some binding authority preventing him from doing so, the owner would instruct a plumber to fit a pipe. The Medical Officer of Health, Dr. J. Battersby said that repeated analyses had shown the water in Joe's Well to be of remarkable purity, but it was a surface stream, though the council had installed tanks and a pipe line to guard against contamination. During the winter, the supply had been frozen for some weeks and the Surveyor had to send water to Low Hill, while in a dry summer the flow was reduced to a trickle. The Council was recommended to seek Ministry advice. In August 1966 it was resolved that the cottages be demolished but the matter was still being debated in the following February. However, we learn in June 1968, a septic tank was to be constructed on Council land and the owners of 12/13, 14 and 15 Low Hill were each to pay 1s per annum for pipes and 5s per annum for a septic tank. These cottages and the old chapel still survive, surrounded by gardens while Moorside Farm isnow an equestrian centre. Only low walls indicate where the demolished cottages stood at Moorside but the three wells, the stones to guide the quarrymen, and a section of the paved road remain (Figures 11 and 12).

Table 1

| 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorside | ||||||

| No. of houses inhabited | 23 | 22 | 21 | 23 | 191 | 13 |

| No. of houses uninhabited | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| No. of inhabitants | 131 | 105 | 99 | 116 | 115 | 64 |

| No. of children under 13 years | 51 | 34 | 27 | 47 | 50 | 18 |

| No. of inhabitants not born in Yorks. | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Low Hill | ||||||

| No. of houses inhabited | 15 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 102 | 10 |

| No. of houses uninhabited | 1 | - | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| No. of inhabitants | 94 | 73 | 43 | 44 | 39 | 26 |

| No. of children under 13 years | 29 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 7 |

| No. of inhabitants not born in Yorks. | 0 | 53 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

1. 6 houses now occupied as 3 (back)

2. 4 houses now occupied as 2 (back)

3. including 3 from Ireland (back)

Back to reference in main text.

Table 2: Occupations of the villagers

| 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | ||||||

| Farmer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Agricultural Labourer | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Gamekeeper | 1 | |||||

| Mining and Stone Working | ||||||

| Miner (Coal) | 5 | 12 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Quarryman/Stone Dresser/Stone Waller | 2 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 2 | |

| Engine Tenter (Stone) | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Textile Workers | ||||||

| Wool combers | 33 | 52 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Weavers | 61 stuff (Worsted) |

9 Handloom (Worsted) |

6 Handloom (Tweed) |

2 Handloom |

||

| (Powerloom) | 16 (Worsted) 7 (Cloth) |

29 (Worsted) |

19 (Worsted) 2 (Woolen) |

21 (Worsted) 3 (Woolen) |

3 (Worsted) |

|

| Factory (Work not specified) | 25 | |||||

| Spinners in factory | 9 | 11 | 15 | 16 | 7 | |

| Warp Dresser | 6 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Other textile workers | 5 Worsted 4 Woolen |

1 Worsted 2 Woolen |

6 Worsted |

|||

Back to reference in main text.

References

1. Sconce was on the opposite side of the small beck and in the parish of Bingley. See About Sconce, by Colin and Margaret Wilson, a booklet produced by the Shipley and Baildon Scout Council, 1984 (back)

2. Telegraph & Argus, letter, 14 October 1983 (back)

3. Martha Atkinson was a member of the Moravian church and religious services were held in her parents' house at Low Hill. She was originally a handloom weaver, but lost employment with the advent of the steam loom. She died in 1879. , Baildon Moravian Church, a brief history, by Winifred Warren, 1983. Typescript (back)

4. putter: one who pushed the coal 'corves' or trucks from the working

hurrier: one who conveyed the 'corves' from the coal face to the bottom of the shaft. O.E.D. (back)

Primary Sources

- Map of the Baildon commons, by Robert Saxton, 1610 (Bradford Central Library)

- Map of the Inclosures call'd the Moor Farms att Bayldon, part of the Estate of Fr. Thompson, Esq., 1737 (Bradford Archives)

- Tithe Award-and Map, 1845 (Bradford Archives)

- Ordnance Survey Maps, 1852-1964 (Bradford Central Library)

- Court Rolls of the Manor of Baildon, 1771-1865 (Bradford Archives)

- Deeds at the Registry of Deeds, West Yorkshire Archives Service, Wakefield: 1803 Vol EP p157; 1836 Vol MK p581; 1838 Vol MW pp303,304; 1841 Vol NY p456; 1855 Vol SY p482; 1858 Vol UF p71; 1862 Vol XE p330; 1878 Vol 812 p329; 1882 Vol 875 p244; 1887 Vol 28 p506; 1890 Vol 14 p529; 1912 Vol 22 p788; 1920 Vol 146 p868; 1923 Vol 79 p1214.

- Land Tax records, Baildon, 1753-1832 (West Yorkshire Archives, Wakefield)

- Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary enquiry into the drainage and supply of water and the sanitary condition of the inhabitants of the township of Baildon, by William Lee, 1852 (Bradford Archives)

- Baildon Moorside Primitive Methodist Chapel records (Bradford Archives)

- Baildon newspaper cuttings, 1899, 1902, 1909, 1910 (Bradford Archives)

- Papers relating to the Bradford Tramways and Improvement Bill, 1899, by which Bradford Corporation purchased Baildon Moor (Bradford Archives)

- Reports of the Medical Officer of Health and Senior Public Health Inspectors for Baildon, 1958-1964 (Bradford Central Library)

- Baildon Urban District Council Minutes, 1962-1974; Baildon Health Committee Minutes, 1961-1974, Baildon Housing Committee Minutes, 1961-972 (Bradford Archives)

- Shipley News

Bibliography

- La Page, J, The story of Baildon, 1951

- Baildon, W P, Baildon and the Baildons: a history of a Yorkshire manor and family. [1924-26]

- Cudworth, W, Condition of the industrial classes of Bradford and district, 1887. Reprinted 1977

- Brears, P, Traditional food in Yorkshire, 1987

- Burrows, D, Baildon - a look at the past, 1985

- Entwistle, N, Pictures of old Baildon, 1985

- Gill, L I, Baildon Memories, 1986

- Baildon Oral History Group, Our Village: loved and remembered, [1990]

Joyce Percy has lived for most of her life in West Yorkshire, attending Whitcliffe Mount, Cleckheaton and Todmorden Grammar Schools. Following a BA Hons degree in History and a Diploma in Archive Administration, both at Liverpool University, she worked as an Archives Assistant at Gloucester City Library before becoming City Archivist at York from 1960 until 1968. While there, she edited a Mediaeval York Memorandum Book which was published in 1973. Joyce retired from her post as Senior Library Assistant at Bradford Libraries in 1999.

© 1999, Joyce W Percy and The Bradford Antiquary