Brunswick Place - Bradford

A study based on the Census 1841 to 1881

Catherine Thackray

(First published in 1986 in volume 2, pp. 1-14, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

Research into family history inevitably leads to a greater knowledge of local history. What follows here is an account of how I became acquainted with a very small area of 19th century Bradford and some of its former inhabitants as I searched for records of my husband's family.

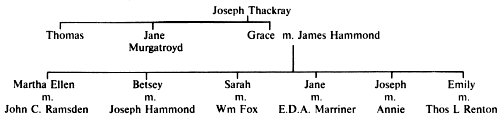

Directories of Bradford revealed that my husband's great-greatgrandfather, Joseph Thackray (1783-1851), stone merchant, was a partner in the firm Cousen & Thackray, quarry owners. Joseph Thackray lived in Shelf but his counting-house was in Brunswick Place, Bradford, where he died of 'a gradual decay of nature', His will of under £7000 indicates that he left the bulk of his property and money, including houses and land in Brunswick Place, to his married daughter, Grace Hammond, in trust for her son, Joseph. There were, however, annuities for his widow (his second wife, not the mother of his children) and another married daughter, Jane Murgatroyd. The residue, possibly only a partnership in the quarries, went to his son, Thomas, my husband's great-grandfather.

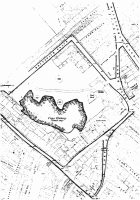

John Wood's 1832 map of Bradford shows 'Thackeray & Cousen' working two quarries near the centre of the town, one of which, Coppy Quarry, was alongside Brunswick Place where there were only two houses. White's Directory of 1837 lists Samuel Mann Cousen, Joseph Thackray's partner, living in nearby Fountain Street, and James Hammond, Thackray's son-in-law, in Brunswick Place; and a Deed of 1834 shows Cousen and Thackray selling land in Brunswick Place to two drapers, William Smith and Thomas Middleton, so it was clearly a developing area.1 When I discovered that almost every resident was listed in White's 1853 Directory I realized that in spite of its position hard by a quarry this was regarded as a good area in which to live, well above the low-lying town centre and away from the polluted canal basin.

Brunswick Place is wedged between a wishbone shape made by the branching of Manningham Lane into North Parade and Northgate on one side, and Westgate on the other. That distinctive shape is recognizable today: James Gate, a narrow lane once known as Fayre Gappe, leads to Northgate and then into North Parade, though Brunswick Place is now flattened and the former quarry has been covered by a car park and a supermarket. Richard Oastler's statue stands looking down on the last remaining row of old buildings in N orthgate, reminding us, perhaps, that in his day the hills could easily be seen beyond the low roof tops. It was the massive Victorian buildings that finally separated Bradford from its rural roots. In the 1830s, according to William Scruton, the space reaching from Brunswick Place to the end of Lumb Lane was one stretch of green fields, in which were fixed posts or 'tenters', for the purpose of drying and stretching cloth.2

In 1832 Brunswick Place hardly existed, but Fountain Street, already built, was described by Winifred Gerin in 1961 as

"still a respectable street, where the residential character of the Georgian house-fronts belies the adaptation of some to commercial purposes [and where once] the brass plates of doctors and solicitors, who together with such clerical gentlemen as Branwell's Uncle Morgan, abounded in the district in the late 1830s."3

For Branwell Bronte lived in Fountain Street in 1838 and 1839, when his 'uncle', William Morgan, was curate of nearby Christ Church. Branwell lodged with Mr and Mrs Kirby, and his portraits of them now hang in Haworth Parsonage. Mr Kirby, an ale and porter merchant, was not perhaps the ideal landlord for Branwell, though it is only fair to say that the Kirbys' niece remembered young Mr Bronte as 'steady, industrious and selfrespecting'. But temptation was at hand in Westgate, noted for its large numbers of inns and beerhouses, conveniently placed for the quarry workers who employed a boy 'several times a day during the summer months in fetching gallons of beer into the quarry'.4

Daphne du Maurier suggests that Branwell's portraits of the Kirbys 'show a genius for satire on the part of the mocking lodger' and that Mrs Kirby 'stares from her frame in disapproval', while her husband's face is 'humorless and suspicious'.5 Mrs Kirby certainly appears formidable but possibly an absence of teeth may have added to the tightness of her mouth. Nevertheless, Mrs Kirby seems to have valued the portraits, because she later asked Branwell to return to varnish them.

Joseph Thackray's first partner was James Cousen, formerly a woollen draper who joined the firm of Rawson, Clayton & Cousen, coal merchants, and became one of Bradford's early Commissioners. He and his wife (nee Mann) attended Horton Lane Chapel where their six sons and two daughters were baptised. They lived at Miry Shay, a fine 17th century house off Barkerend Road, and for a period at nearby Boldshay Hall. James Cousen died at Miry Shay in 1844, and his son, John, was born there in 1804. Maria Branwell, writing from Woodhouse Grove School to her fiance, the Rev. Patrick Bronte, in September 1812, said she had spent the day at Miry Shay. Shortly afterwards she wrote again saying that several families of 'Bradford folks' had visited Woodhouse Grove, and although she does not mention them by name it seems likely that the Cousens were in the party.6

Of James Cousen's six sons several went into the quarrying business, Samuel becoming Joseph Thackray's partner, but two of the brothers were well known local artists, friends of Geller, Bentley and Branwell Bronte.

John Cousen was described by Butler Wood as 'one of the ablest landscape engravers of the century … a Turner engraver par excellence',7 and he was of sufficient standing to be accorded an obituary notice in the Times. The frontispiece to John James's History & Topography of Bradford - a south-east view of the town - is an engraving by John Cousen from a drawing by Charles, his brother and pupil. 'Bierley Hall', in Scruton's Pen & Pencil Pictures, is also drawn by Charles but engraved by J.C. Bentley. A long list of the works of the two brothers, most of which appeared in art journals of the period, includes two engravings by Charles of simple cottage interiors, which I came across in an antiquarian bookshop - and now own.

The 1841 Census shows that there were then sixteen houses in Brunswick Place and that many of the residents, including William Smith and John Milligan, were Scottish. These two were wool merchants, the latter being the brother of Robert Milligan, Bradford's first mayor, and later one of its M.P.s. From a modest start as a draper, Robert Milligan, in partnership with John Forbes, built up the firm of Milligan, Forbes & Co., becoming one of Bradford's most prosperous merchants. James Rennie, Robert's brother-in-law, also lived in Brunswick Place in the late 1830s. Other residents in 1841 included William Jackson, schoolmaster, John Caldwell, editor, and the Rev. J. Goodeve Miall, who was the first minister of Salem Congregationai Chapel in Manor Row, a building now used as offices. On arriving in Bradford Mr Miall feared he would never endure the climate, saying later, 'I used to feel as if I would go mad', but he stayed for over forty years, becoming an active member of the Mechanics' Institute and a much respected minister and writer. His obituary in the Bradford Observer states that he loved archives, disliked visiting and had no particular gift for conversation.8 The list of mourners at Mr Miall's funeral in 1896 includes the names of persons who had been children living in Brunswick Place fifty years earlier. Mrs Miall, nee Mackenzie, was the aunt of Sir Morell Mackenzie and great-aunt of the author Compton Mackenzie and actress Fay Compton. One of the Miall sons was the brilliant agnostic scientist, Louis Miall, of Leeds University, who as a young man was the first Curator and Secretary of Bradford Philosophical Society. Mr Miall's stepbrother, Edward Miall, who became M.P. for Bradford, was a leading campaigner for the disestablishment of Church from State.

Salem Chapel opened in 1835 and among its first members were the Salts and Milligans - and Isaac Kirby, Branwell's former landlord, who was interred there, aged 44, in 1848. It was said that when the number of Salem Chapel places was increased in the l840s, by putting the pews closer together, some of the old seat-holders resented the interference and left. One member of Salem Chapel was James Hammond, Joseph Thackray's son-in-law, whose little daughter's name is recorded in the 1839 interments. In 1841 this family consisted of the parents and four young girls, including six-month old twins, and with them was Jane Murgatroyd, described as 'Family Servant' but in fact Grace Hammond's sister.

Among the many Deeds relating to the Cousen & Thackray quarries is one of 1823 recording the sale of land to Titus Salt of Hunslet and his son, Daniel, grandfather and father of Sir Titus, respectively.9 The Salts had opened a small warehouse in Bradford in 1822 and came to live in North Parade, alongside Brunswick Place. In his life of Sir Titus Salt, Balgarnie, a personal friend, tells how Salt learned every aspect of the wool trade at Rouse's mill, mainly from two brothers, John and James Hammond. There is a note of intimacy in the episodes relating to the Hammonds, particularly the one in which Salt proposed that John Hammond should join him in his new venture. Hammond refused on the grounds that Rouse had always been good to him. Salt concluded, 'Well, John, I am going into this alpaca affair right and left, and I'll either make myself a man or a mouse.,10 Mr Balgarnie added the information that both the Hammond brothers were remembered in Rouse's will, and this naturally led me to look into the Rouse bequest.

William Rouse started a top-making business in Bradford in the 1780s, but it was not until 1815, when his son joined him in partnership, that the mill really flourished. In those early days they employed over fifteen hundred handcombers, who could be seen

"coming periodically to the mill from all the countryside, bringing the prepared material on donkeys and by other conveyances, most frequently on their own broad backs."

John Rouse was described as

"a man of considerable business parts and was mainly instrumental in building up a connection which was regarded as about the largest and most important in the West Riding - the whole trade was in the hands of Rouse and two or three other firms."11

John Rouse died in 1838, predeceasing his father, and left £70,000 of which £2,000 and two annuities went to John Hammond and his wife Maria, 'in testimony of my regard for him and in consideration of the unremitting exertions he has made in my service for a period of 20 years', and £1,000 to James Hammond, his good friend and general manager. There were also bequests of £200 each to Kirkgate and Eastbrook Chapels. The Rouses are said to have been good employers, their motto being, 'Those who have helped us to get money shall help us enjoy it'. This may have applied at management level, but there is no evidence that the mill workers benefited. Rouse certainly helped to found a Friendly Society, but he was among those employers who met at the Sun Inn in 1825, during the wool combers' strike, and agreed not to employ any comber who continued as a member of the Union.

W.E. Stamp said of John Rouse,

"His career as a Wesleyan Methodist was marked by a pious solicitude for the spiritual interests of his relatives, and by an anxious concern for the instruction and welfare of the children of the poor; for whom he provides a week-day and two Sabbath Schools."12

But Horace Hird contended that 'it was Mr Rouse and Mr Leather, owners of two of the largest mills in the district, who had such mistaken ideas about godliness and where it was to be found'. Half-timers were threatened with dismissal unless they transferred from Wapping Road School to the Parish Church School.13 John Rouse's epitaph at Kirkgate Chapel read, 'DILIGENT IN BUSINESS, FERVENT IN SPIRIT, SERVING THE LORD'. The priorities are interesting.

Balgarnie's book brought to light new facts which made it possible to trace earlier members of the Hammond family who attended the Congregational Chapel at Horton Lane. James Hammond's cousin was the innkeeper of the Market Tavern and father of Ezra Waugh Hammond, later Alderman of Bradford and Chairman of Yorkshire Brewers. Both families attended Salem Chapel and Ezra Waugh served an apprenticeship with Rouse & Co. Jonas Hammond of Round Thorn, Girlington - another of James's cousins - wrote a delightful account of the birth of unexpected twin sons to his grandparents in 1768. He provides a vivid picture of what this must have meant to a simple and hardworking couple who already had a large family and how the neighbours rallied to help them.'14 Twins are a recurring feature in the Hammond family - the deaths of Albert and Edward, infant sons of Joseph Hammond of Brunswick Place, were announced in the Bradford Observer in 1863.

It seemed obvious that Joseph Thackray's legacy to his Hammond daughter and grandson was not due to any financial need on their part, because they had already received the Rouse bequest. This view was slightly modified, however, when I learnt that in the 1840s, after the death of old William Rouse, a long and costly Chancery suit, following a dispute between the three remaining Rouse brothers, caused the mill to be closed down for two years and created much distress among the hands. By order of the Court the mill was divided and auctioned in 1847, the larger part being knocked down to Titus Salt who, to everyone's surprise, was found to be simply bidding on behalf of William Rouse Junior. The mill once again flourished and James Hammond became William Rouse's partner.

With so many Scottish people in Brunswick Place, it is not surprising that the new Scots Kirk with 700 sittings was built in 1840 in Simes Street, a continuation of Fountain Street and lying next to Brunswick Place. No doubt financial help came from local residents. Another development within half a mile of the quarry was the building, in 1843, of the new Bradford Infirmary for 60 in-patients, a replacement for the much smaller premises in Darley Street, but it was soon found to be inadequate for the needs of the growing population.15 Nine years later Undercliffe Cemetery, a private burial ground for the elite of Bradford was opened. It was used not only for interment but as a place where 'the quality', like the people of Brunswick Place, could promenade at their leisure.

By 1851 the number of residents in Brunswick Place had grown to 134, almost double the count taken ten years earlier, with an increase of only five more houses. Nearly all the households had one family servant, and some had two. Most of the men were 'in wool', either as worsted spinners, manufacturers, woolstaplers, wool dealers or drapers. The only women in paid employment, apart from servants, were dressmakers, milliners and shop assistants, who were part of their employers' households, at a time when large drapers' shops in Bradford were open 8am to 9pm, Monday to Friday, and till midnight on Saturday. The majority of households in Brunswick Place in 1851 consisted of people born outside Bradford, an indication of the extent of immigration. One of these was William Addison, clerk to the Railway Goods Department, born in Cumberland, whose eldest son, aged 19, was a guard. This is a reminder that the railway had arrived in Bradford in 1846 and that its employees were expected to be mobile - Mr Addison's eleven children were born in Manchester, Hull, Brighouse and Leeds.

The Bradford Eye and Ear Institution, which opened in 1857 at 25 Brunswick Place, had its origin in a small private dispensary run by Dr Edward Bronner. Subscriptions from a number of prominent local people enabled a committee to rent the new premises in order to give 'gratuitous advice' to the poor, suffering from diseases of the eye and ear, and Dr Bronner became the first Medical Officer. Since the 1861 Census shows the residents as Sarah Overend (nurse) and Thomas Eveleith (born Devonshire) her only patient, it seems that the Institution catered mainly for outpatients, and the premises soon became inadequate. They were replaced by a new building in Hallfield Road - the Bradford Eye and Ear Hospital - in which much pioneer work was done, particularly towards prevention of blindness at birth. The move took place in 1865 and the house in Brunswick Place became an Industrial Home for Orphan Girls, taking in sixteen girls orphaned by an explosion at Oaks Colliery, Barnsley. Its purpose was to receive friendless girls and train them for domestic service. This large house was probably the one listed in 1845 as John Gamble's Factory School and in 1871 as a Servants' Registry Office.

On the 1871 Census there was no sign of the Hammond family, which had been the focus of my interest in Brunswick Place. They had lived there for thirty years and at two periods had a married daughter next door at No.14, but now they had gone. The will of James Hammond showed that he had died in 1867, leaving £60,000 and naming his only son, Joseph, chief legatee, with substantial bequests to his widow, four married daughters and his youngest unmarried daughter, Emily, whose educational costs had to be met. (One of the witnesses to the will was William Scruton, the well-known local historian, then a solicitor's clerk). The will revealed the names of his four sons-in-law, all of whom proved to be wool merchants. In spite of their Congregational upbringing all four daughters were married at four different fashionable Anglican churches in Bradford, Ilkley, Bolton Abbey and Calverley - examples of what Dr Binfield aptly described as, 'marriages which united pews and fortunes as well as hearts'.16

The families of all four in-laws, which were easy to find, provided further points of interest. At Undercliffe Cemetery, alongside the main promenade, stands a tall obelisk to Alderman John Ramsden and his family, including his son, John Carter Ramsden of Gristhorpe Hall, Filey, husband of the eldest Hammond daughter, Martha. Alderman Ramsden died at Scarborough in 1867 and according to his obituary, 'he was a man of good natural powers but had few early advantages, he learnt the valuable lesson that self-cultivation is better than houses and land.'

Jane Hammond, one of the twins, married Edward D.A. Marriner of Greengates Mill, Keighley - magistrate, councillor and, in 1885, Mayor of Keighley. This family is well documented, partly because Benjamin Flesher Marriner, Edward's father, developed the highly successful mill and married the heiress of the Lister family of Frizinghall. He and his bachelor brother, William, seem to have been successful in all they touched, which included among other things founding a Savings Bank and the Keighley Brass Band. But the other side of the story is the extraordinary family feud between Benjamin's two sons, Edward and his elder brother, William, which led to a complete severance of relations and a physical division of the mill.17

By the 1860s the character of Brunswick Place was changing. A road improvement map of 1867 showed that No.22 was to be knocked down, enabling Infirmary Street to lead directly off Brunswick Place. In 1871 a solicitor and his eight children were living in the Hammond's old house at No.16 and with him was Harry Harrison, his son-in-law, a comedian, for Pullan's Music Hall had opened in Brunswick Place in 1867 and several of the households now had 'artists' and 'vocalists' lodging with them. The Music Hall was a large wooden building 120 feet long by 72 feet wide holding 3000 people and producing 'respectable shows' for the skilled working class. But it is unlikely to have been approved by the even more respectable residents of the area.18 A few surviving programmes reveal that the artists were mostly vocalists, comic or serio-comic, with the occasional more exotic performer, like 'Mons. Grovini', contortionist; 'Mons. Leroni', boneless wonder and man with iron jaw; 'Messrs. Henri and Charlan', clowns and gymnasts and 'Mme. Colonna' and her troupe of Parisian dancers. Two of the vocalists shown in a programme - Joseph and Marie Taaff - were actually living in Brunswick Place at the time of the 1871 Census. Henry Pullan, proprietor, and his son Christopher, manager, lived at No.14 Brunswick Place and their graves are in Undercliffe Cemetery. In 1877 the first Salvation Army meeting in Bradford was held in Pullan's Music Hall, and in spite of much opposition over 600 people were converted in the first year of the Army's campaign. In 1881 Henry Pullan was before the magistrates concerning the matter of another exit in case of fire, 'there being only one large door, at the side, of 9ft and wooden buildings nearby which if they caught fire would prove a source of danger'. Eight years later these fears were confirmed when the building was burnt down in what were described as mysterious circumstances, but by then it had become vacant.

The filling-in of Coppy Quarry, which had become a dangerous nuisance, enabled the Music Hall to be built on the site, but the waste ground around it was still called Coppy Quarry and the 1871 Census showed that living on it were James Walsh, born Ireland, and wife, with their travelling shooting gallery. The waste ground continued to be used for travelling fairs, and Chris Thompson's travelling circus came for the winter months about 1916-1919. Later it was used for an open market known as the Quack Market. When in 1960 the foundations were laid for the new Car Park and Supermarket there were many problems to overcome 'not the least being due to the fact that the site was previously the old Coppy Quarry which was some 10Oft deep and filled with loose material' - strong enough for Mr Pullan's light wooden building but providing no firm base for twentieth century shoppers and their cars.19

In 1877 the Quakers decided to build a new Meeting House fronting on Fountain Street and going right through to Brunswick Place but the site was described as 'a peculiar one for such a valuable range of premises'. At the opening celebrations 'Messrs Davis and Gilpin of the Post Office made experiments with the latest wonder, the telephone, which was fairly successful in a circuit of about a quarter of a mile' and 'Mr Bottomley gave a magic lantern entertainment to the young people'. In addition 'the large schoolroom was fitted with carpeting of crimson cloth and tables covered with green baize by Messrs C. Pratt and Son'. Christopher Pratt's still stands in Rawson Road, once Brunswick Place. The former Quaker Meeting House 'a chaste, ample and substantial building in Italian style', by Lockwood and Mawson, is now Gatsbys Night Club - a strange transformation.20

An undated Guide to Bradford - probably circa 1920 - shows Victoria House, Brunswick Place, advertising Turkish Baths, with the information that Thursday was reserved for ladies only, and a wing was for 'commercial gentlemen and others staying temporarily in the city who may have baths free of charge'. It was a corner house in a terraced street, and when in the Bradford Archives I came across a Sale Notice dated 1881 concerning the property in Brunswick Place and Simes Street 'rented at £30 p.a. by Mr Fawthrop Fyrth M.R.C.V.S', I felt sure that this was the same building. A Directory of 1880-81 shows John Fawthrop Fyrth, 18 Brunswick Place, with a shop in Northgate and owning houses in Northgate and Thornton. He was a grandson of Dr. Fawthrop Fyrth of Thornton and the son of Thomas Fawthrop Fyrth, who was also a vet, referred to by Burnley as one 'who mends broken bones, the maimed and the halt coming thither in large numbers, especially on market days,.21 Thomas, who had been apprenticed to his father, the doctor, could deal with both animals and humans. He was a prominent Conservative and gave his walking-stick to Randolph Churchillby such strange deeds are we remembered. The Fyrth family grave is at Undercliffe, and as John's daughter, Mrs Pownall, was a masseuse, it seems likely that it was she who ran the Turkish Baths.

Initially, I overlooked some words in very small print on the Sale Notice, 'by the will of the late Mrs Grace Sutcliffe'. On checking the Census lists I found that there were two Sutcliffes living in Brunswick Place in 1851, one a bachelor, the other with a wife called Sarah. The Index of Wills at Wakefield showed that Mrs Grace Sutcliffe of No.2 Oak Villas, Manningham, had died in May 1881 and that her executors 'were Abraham Best, woolstapler, and Frederick Shaw Harwood, bookkeeper - the same two men who had executed James Hammond's will in 1867. The will proved to be a most interesting and personal document. This was indeed Grace Hammond, nee Thackray, now Sutcliffe, who died leaving a personal estate of £8000. She detailed the contents of each room in bequests to her daughters and her son, including portraits in oil of Mr Rouse and Mr and Mrs Hammond, but one daughter, Sarah Fox, simply received £25 in lieu of furniture, and all her underclothing. Perhaps Sarah had all the furniture she needed.

Grace's second husband emerged as Samuel Sutcliffe, the married neighbour of twenty years earlier. He was a wool merchant who owned Valley Mills and for three years a local Councillor. He was also a devout Congregationalist who in the early days of Salem Chapel had fitted up a room at Valley Mill for a Sunday School.22 Samuel left £14,000 and two houses in Manningham, the tenant of one of them being a former resident of Brunswick Place, Andrew McKean, whose portrait was one of those painted by John Sowden and now at Bolling Hall. Samuel Sutcliffe's property went to his children but he made no mention of Grace. The marriage between Samuel Sutcliffe and Grace Hammond took place in Scarborough in 1871, the ceremony being performed by the minister of South Cliff Congregational Church, none other than the Rev. Robert Balgarnie. The two witnesses were Martha Balgarnie and Jane Murgatroyd, the minister's wife and the bride's sister. Clearly Mr Balgarnie knew both the Salts and the Hammonds well, for John and Maria Hammond, legatees of John Rouse, retired to Scarborough and no doubt talked to him while he was writing his life of Salt. Their daughter, Mary, died in 1866, while staying with her Uncle James and Aunt Grace in Brunswick Place, so the ties between these brothers seem to have remained close. South Cliff Church, designed by Lockwood and Mawson, and opened by Salt, was described as the 'Congregational Cathedral of the North'. It appears that Grace, like her daughters, chose marriage in a fashionable church.23 When in 1984 I visited Scarborough and asked in a newsagent's shop for directions to the Congregational or United Reformed Church, the reply was 'I don't know about those but I can direct you to what we call Balgarnie's Church'. Nearly a century after Mr Balgarnie left his ministry in Scarborough his name lives on.

The 1881 Census showed that only two residents had lived in Brunswick Place longer than ten years and both had changed their occupations, one from groom to gardener, the other, who was the only remaining Scotsman in the road, had been a draper but was now a wine salesman. There were a large number of vocalists, three comedians and several musicians. Such people as remained from the wool trade were no longer merchants but a draper's traveller, a cloth miller, a mantle maker, an upholsterer, a warp dresser and a woollen waste dealer. Most of the houses were shared, and though as a result of demolition the number of houses was reduced, the residents had increased to 155 compared with 79 forty years earlier. The street had clearly come down in the world. Many of the former residents had moved out to Manningham, among whom was Grace Sutcliffe, living at 2 Oak Villas, where she died a few weeks after the 1881 Census was taken. With her during the Census were her sister, Jane Murgatroyd; her son, Joseph Hammond, aged 38, retired iron founder; her granddaughter, Grace Ramsden, 25, 'companion', and a cook and a housemaid. When seen in 1983 her house was falling into decay, but No.2 Oak Villas is now converted into flats, and much altered from the comfortable semi-detached house with an attractive frontage formerly hidden behind trees. But the quiet, tree-lined road near the park remains as it was in the days when Grace and the Town Clerk and many German merchants lived there.24 From the details given in her will it is possible to visualize the interior of Grace Sutcliffe's house the four post mahogany bedstead and bedding in the bedroom over the drawing room (known as my bedroom), the iron bedstead and bedding with crimson curtains in the bedroom over the kitchen, the time piece upon the dining room mantle shelf made by J. Vassali, the dark oak table under the window in the dressing room upstairs, the invalid couch by Robinson of Ilkley, the hat stand with marble top, the piano chiffonier and ornaments on top.

Jane Murgatroyd outlived her sister by ten years, having had valvular disease of the heart for twenty years. Her death was reported by her niece actually a great-niece - Ida Fox, and she is described as 'wife of Charles Murgatroyd, a commercial clerk'. Jane and her husband were living in the same house at her death, in spite of the fact that at every census she appears to have been with her sister Grace.

In the lovely little village of Gristhorpe, near Filey, stands the fine looking hall belonging to the Beswick family, but once occupied by Grace's eldest daughter, Martha Ramsden, and her family. On the 1881 Census for Scarborough and Filey, Martha Ramsden had with her her son, 'a sailor's mate, seaman', three of her four daughters and their governess, a cook and a housemaid. Her husband is described as 'Inventor pure science'. The Index at the Patents Library, Bradford, showed that J. Carter Ramsden had patented inventions regularly for thirty years, all relating to mill machines.

Samuel Sutcliffe died in Bradford in 1871, only five months after their marriage, but Grace was in Scarborough for the Census taken shortly before the wedding. She was located at Mount Royd Villa with a young visitor from Bradford - Alice Beaumont - and a cook and housemaid. Next door at Mount Royd Cottage was Mr Cordingley, born in Bradford, and describing himself as 'coachman to Mr Hammond'. The Balgarnie family were in the neighbourhood and so, unexpectedly, were Jane and Charles Murgatroyd with two visitors from Bradford, Charles Murgatroyd's twenty-year-old niece, and Ida Fox, aged eleven months.

Facts are still coming to light about Grace's daughters. Emily, who was her mother's companion at the time of her father's death, remained in Bradford. She married Thomas Leavens Renton, a woolstapler, and the deaths of two small daughters - one at Scarborough - are recorded in the Bradford Observer. Emily and her husband are interred in Scholemoor Cemetery, with the inscription 'In death they are not divided'. They died in 1920 and 1921 and Emily's will proved as interesting as her mother's. She too had lovingly listed all her treasures - the clocks, pictures, piano and even the fish carvers. One of the properties mentioned is 'the house left me by my late mother Grace Sutcliffe, 2 Oak Villas'. But more personally interesting are her references to 'the photo of my boys' left to her son Thomas, one of her seven children; 'the pieces of plate presented to me by Bradford Thespian Society'; 'the portrait in oils of my father and mother' left to her daughter, Alice Hammond Anderton, and a photograph of her parents left to her daughter, Mabel Marian Barnard (or Bernhard). There is a likelihood that these portraits are still cherished by someone in Bradford.

It proved possible to follow up the references to the Thespian Society even though there are only two small books of Rules and List of Members relating to the Society, in Bradford Library. They cover the years 1888 and 1889 and show that a member of the Ladies' Committee was Mrs T. Leavens Renton. The Ladies' duties, apart from assisting the Gentlemen's Committee, were to control all questions relating to lady performers, including dress, and to appoint at least two chaperons to attend rehearsals. Among the long list of members several things are noticeable; the very high proportion of German names and the many family memberships - often as many as four or five from one family. Almost all Grace Sutcliffe's neighbours in Oak Villas are there, including the Town Clerk, and there are at least eighteen relations of Emily Renton.

My interest initially centred round one family and the area in which they lived, and the members gradually emerged as individuals who unconsciously reflected their times. Those early residents of Brunswick Place shared with John Hammond a life whose 'unremitting exertions' for their employers and their chapels brought material rewards, but even when they moved to larger houses in Manningham their way of life does not appear to have altered drastically. They remained a close-knit group attached to a few nonconformist chapels, enjoying their holidays at Scarborough, which for them was 'Bradford-by-the-sea', and many remained neighbours to the end of their days. Unlike some of the early industrialists they were not spendthrift but 'careful and prudent in management and business' like the successful Robert Milligan.25 Their absorption in work and religion is well illustrated in the Holden family letters, where references to combs and noils vie with phrases like 'the throne of grace' and 'the crown of life'. Even after retirement Angus Holden could write, 'It seems that when I come within sound of our dear old combing machines, the old passion comes over me and I cannot keep aloof. They were equally - and passionately - at home in both worlds. Their values and way of life are foreign to us, but it is perhaps the strangeness of it all that intrigues us, as the continental names did the music-hall audiences.

The emergence of Bradford as a leading textile town was greatly helped by the close personal ties of its most important families, through marriages which owed as much to the women as the men. Men pass on a name, and sometimes money, but women pass on traditions and occasionally much-prized possessions. It was the women in this story who made Brunswick Place come alive for me, and with it the realization that the history of 19th century Bradford has been told too often through its men.

References

1. Deed 1834 (Wakefield) BK LZ p.406, No.386. (back)

2. >W. Scruton, Pen & Pencil Pictures Of Old Bradford, 1889. p.208. (back)

3. >W. Gerin, Branwell Bronte, 1961, p.141. (back)

4. >W. Cudworth, Condition Of the Industrial Classes Of Bradford, 1887, p.86. (back)

5. >. du Maurier,

6. >J. Lock & W.T. Dixon, A Man Of Sorrow - Patrick Bronte, 1965, p.130-32. (back)

7. >Butler Wood, "Some Old Bradford Artists", Bradford Antiquary, O.S. vol.2, p.203. (back)

8. Bradford Observer, 17.2.1896. (back)

9. Deed 1823 (Wakefield) BK HU, p.281, No.257. (back)

10. >R. Balgarnie, Sir Titus Salt, 1877, p.70. (back)

11. Bradford Weekly Telegraph, 25.9.1886. (back)

12. >W. Stamp, Historical Notes Of Wesleyan Methodism in Bradford, 1841, p.92. (back)

13. >H. Hird, Bradford Remembrancer 1972, p.192. (back)

14. Preston Papers, Bradford Central Library, Box 2/7. (back)

15. >J. James, Continuation & Additions to the History Of Bradford, 1866; Scolar Press, 1973. p.212. (back)

16. >D.G. Wright, "Mid-Victorian Bradford: 1850-1880", Bradford Antiquary N.S. Pt.XLVII, 1982, p.77. (back)

17. >G. Ingle, History of R.V. Marriner Ltd, Leeds M.Phil thesis, 1974. (back)

18. Fred Jowett remembered that it was mainly the young people who visited the Music Hall. Older people were more interested in the legitimate stage. See >A.F. Brockway (ed), Socialism over Sixty Years, 1946. (back)

19. See Telegraph & Argus, Bradford, 3.8.1969, for the opening of John Street Market. When Rawson Place Market was opened in 1875 'the honour of making the first sale was reserved for Mr James Wignall, butter factor, one of the oldest tradesmen in the market'. He lived in Brunswick Place. (back)

20. >H.R. Hodgson, The Society Of Friends in Bradford. 1926, p.63, but G. Field, in a lecture in 1903, described the premises as 'second to none in England for the purpose of our various meetings'. (back)

21. >J. Burnley, "The Streets of Bradford", Bradford Observer, 1883 (Extracts), Bradford Central Library. (back)

22. >J.G. Miall, Congregationalism in Yorkshire, 1868. p.237. (back)

23. Scarborough Gazette, 27.7.1865. (back)

24. Another neighbour in Oak Villas was Mr Appleton, formerly of Brunswick Place. He was a photographer and several of the photographs in Bradford Portraits (>J.R. Beckett ed) 1892, were taken by him. (back)

25. Richard Wilson, a mill worker, gave evidence concerning Richard Fawcett. 'the founder of the worsted trade', who had gone bankrupt. He said, 'He saved £5000 a year, besides keeping his own family; and then if there was anything to buy, he bought it all round him, however little it paid him, and in a length of time he came to ruin …. it was not his worsted mill that beggared him.'

Committee on Factory Children's Labour, P.P.1831-32, vol.XV, p.129. (back)

© 1986, Catherine Thackray and The Bradford Antiquary