The Walls of Jericho at Egypt, Thornton, Bradford

Alison C. Armstrong

(First published in 1985 in volume 1, pp. 44-49, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

"Ordinary tourists might be content to know that Halifax is reachable that way, but with even less effort may be visited Moscow, Egypt, Jerusalem and the World's End."

William Cudworth, Round About Bradford.

In his description of Thornton, from which the above passage is taken, Cudworth goes on in his quaint fashion to say,

It is notable that all these places are very stony regions; the Egyptians, unlike their eastern namesakes, being especially well off in this respect.1

At that time - 1876 - he says there were about thirty quarries in the district, employing a total of 450 workers, including some boys only eight years old.

Motorists and pedestrians passing through these 'stony regions' may have made their way up or down Egypt Road, between the towering Walls of Jericho, amused by the name and possibly wondering why structures of such a height were necessary. The walls seem to close in on the narrow road with its steep hairpin bend, creating at times an atmosphere of eeriness and claustrophobia. We are not sure when the biblical nickname was first coined, but as Cudworth does not include it in his 'gazetteer' it must have been after 1876. The name may be the result of association with Egypt Methodist Chapel, now demolished, but it is of no great antiquity. The first 'literary' mention occurs in Elizabeth Southwart's Bronte Moors and Villages, published in 1923.2 Egypt, the small hamlet at the lower end of the walls, first appears as a place-name on the 1847-50 Ordnance Survey Map,3 but the settlement was established earlier in that century. Kendall & Wroot suggest that it commemorates the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon in 1798.4

Motorists and pedestrians passing through these 'stony regions' may have made their way up or down Egypt Road, between the towering Walls of Jericho, amused by the name and possibly wondering why structures of such a height were necessary. The walls seem to close in on the narrow road with its steep hairpin bend, creating at times an atmosphere of eeriness and claustrophobia. We are not sure when the biblical nickname was first coined, but as Cudworth does not include it in his 'gazetteer' it must have been after 1876. The name may be the result of association with Egypt Methodist Chapel, now demolished, but it is of no great antiquity. The first 'literary' mention occurs in Elizabeth Southwart's Bronte Moors and Villages, published in 1923.2 Egypt, the small hamlet at the lower end of the walls, first appears as a place-name on the 1847-50 Ordnance Survey Map,3 but the settlement was established earlier in that century. Kendall & Wroot suggest that it commemorates the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon in 1798.4

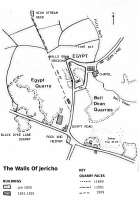

We are used to seeing the holes and hollows left in the ground after quarrying, but what happened to all the waste after the stone had been removed is not easily apparent. The Walls of Jericho provide one answer, because these high judd ramparts were built to hold up the mounds of waste rock thrown up from the quarries on each side of Egypt Road. The old Bell Dean quarry to the east is now infilled and landscaped, while Egypt quarry on the west is a deep, disused hole some distance from the original delph. Few documents exist to tell us about the activities of the two quarries which made the walls necessary, but there are some clues. One lies in the contours of the adjacent land, which are very different from those mapped in 1847-50. Since then waste has been tipped on to the fields and the exhausted areas have been back-filled as the quarry faces progressed.

Stone was generally used for domestic building in the Bradford area from the mid-seventeenth century. By the eighteenth century, quarry and masonry methods improved and landowners' accounts indicate much rebuilding in stone, and the opening up of delphs for wallstones. From the l790s until the early nineteenth century numerous active delphs were providing stone for enclosure walls, mills and housing. The early quarries at Bell Dean and Egypt probably opened to meet this growing demand. Elland Flags sandstone from the Carboniferous Coal Measures could be worked where it outcropped on the hillside above Bell Dean.

The 1771 Enclosure map for Thornton indicates that the hamlet of Egypt and the quarries did not then exist.5 Egypt Road was a thoroughfare to Allerton with a hairpin bend on the steepest part of the descent, now the site of the walls of Jericho. The footpath from Egypt Road, avoiding the bend, provided a short cut, as it still does, creating an 'island', which now contains a field and some cottages. In about 1600, however, part of the island plot had been enclosed and may have been used for stone-getting. The island later became the northern part of Bell Dean quarries.

By the early nineteenth century the enclosed land in the neighbourhood was colonised with farmsteads and the new hamlets of Moscow, Egypt and Thornton Heights grew and flourished. Baines Gazetteer of 1822 lists four quarry owners and two masons at Thornton. White's Directory of )838 lists the Rock and Heifer Inn and six quarry owners, with the comment, 'Thornton Heights has excellent stone quarries'. There is a datestone 'J S A 1820' on cottages opposite the Rock and Heifer, which perhaps commemorates Jonathan Ackroyd, quarry owner at Heights. These cottages, which may have been built for quarry workers, are very similar in construction and detail to the back-to-back cottages at Egypt, with their square-profile, stone mullion windows and door surrounds. Another house, which disappeared by 1890, was built in the northern corner of the hairpin bend some time before 1850, when the Bell Dean and Egypt quarries were certainly active. William Cudworth points out that Thornton Heights stone was even sent to Queensbury in 1843, since no effective quarrying was taking place there at that time.

The Ordnance Survey Map of 1847-506 shows that Egypt quarry consisted of two delphs, each about 25 feet deep and lying off the west side of Egypt Road above the bend. Bell Dean quarries on the east side of the road were also in two parts, separated by the lane (now a public right of way). The island plot was worked right up to the edge of Egypt Road, while to the south the other quarry face had cut back into the hillside and was some 50 feet deep.

A careful study of the map contours and field boundary changes since 1771, together with field observation, strongly suggests that by 1847-50 parts of the walls were already formed and retaining quarry debris, which is usually tipped downhill from the site. This waste consists of 'baring', that is the top layers of useless, weathered rock and soil, unusable current-bedded 'fioity' sandstone, and quantities of muddy and sandy shale which lie between the good lifts of sandstone. From the island plot of Bell Dean quarry the waste would naturally be tipped down towards the cottages and the road near the beck, making a judd wall essential on the lower side of the land to keep the roads and adjoining properties clear of debris. The sudden bend of the contour and change of field boundary shape since 1771 indicates that a judd wall probably existed from the bend, running east along the roadside and turning south along the edge of the island plot near the cottages. At this comer the contours indicate a wall 15 feet high.

Similarly, waste from the roadside delph at Egypt quarry would be tipped towards Egypt Road. A judd wall of small stones, which lies above the bend near a small copse, follows the road and curves away into the field around the site of this quarry and may represent the earlier wall. From the second delph of Egypt quarry, waste seems to have been tipped northwards and down into a small valley (now buried), causing the Stream Head footpath to bend around it. This tipping was later to encroach upon the whole field.

From about 1860 the stone industry boomed in the Bradford area, giving rise to investment in steam-powered machinery for lifting, transporting and sawing, and quarry owners became successful businessmen. Moulson, Farrar and Thackray, who quarried at Thornton Heights, were well known in the trade. At the Bell Dean and Egypt quarries stone-getting must have increased dramatically from this period, for by 1891 the Walls of Jericho were completed and the Bell Dean quarries exhausted.

A land-ownership plan dating between 1850 and 1873 shows that the Bell Dean quarries were on land belonging to Mrs Smith, who may have been a relation of Francis Sharp Powell, a former owner.7 The land was probably leased for quarrying and no records survive, but leases usually required that land should be reinstated after stone extraction and breast or burr walls built if necessary. On Mrs Smith's plan the island plot is owned by quarrymen Cousen and Thackray, although no active quarry is shown and it may have been infilliand. The big quarry face at Bell Dean is much as it was in 1847-50 and the mound of waste is named 'Rubbish Hill'. The house on the hairpin bend was still there. It is significant, however, that the line of the present walls is shown as a broken line, indicating that they are not normal field boundaries. Since the cottage north of the corner is shown, the walls could not have reached their final extent. On the island plot, however, the disappearance of a small building, and the rounding of the corner at the bend since 1847-50, suggests that the judd walls on the east side may have been complete.

A sale plan dated. 1873 shows that Bell Dean quarry face was 78 feet high.8 Of this, 32½ feet was baring and 24 feet floity stone, indicating that a lot of waste had been disposed of. The quarry almost reached Lower Heights Road and must have been nearing exhaustion. It was worked by John Farrar & Son to the east, and William Moulson to the west.

By 1891 the whole of Bell Dean quarries had been inf1l1ed, the field walls rebuilt and new cottages erected on the reclaimed island plot.9 A close look at the stonework of the Walls of Jericho bounding the island indicates one period of building, with the exception of the eastern end already mentioned. Large foundation blocks protrude through the tarmac, and the wallstones, which are larger at the base than the top, are of uniform, sharp-edged 'nell' throughout. There is no evidence of tooling, although frame-sawn and other kinds of block have been used at a later date to infill and buttress the cavity at the base of the bulging wall.

It is curious that Egypt quarry rarely appears in written sources, but like Bell Dean quarries it expanded rapidly, and by 1891 the face had almost reached Black Dyke Lane. The extracted area had been backfilled as the work progressed, while mountains of excess waste had been tipped directly into the small valley to the north, eventually encroaching on and burying the corner house and its coal pits. The walls around and over the newly-levelled fields were rebuilt before 1891 and the High Stream Head footpath straightened. Part of a coal pit can still be seen in an adjoining field which was untouched by quarry tipping.

A close look at the Walls of Jericho on the Egypt quarry side, below the hairpin bend, indicates three distinct periods of heightening and lengthening. The earliest judd wall, as already mentioned, was probably well above the bend, but at the base of the bend itself there is a low, sloping wall of small, flaggy blocks bearing stress cracks from the weight overhead. Above and beyond this is a sloping wall of large blocks of floity stone indicating a further extension. When this was built the old corner house was completely buried. Finally there was a great extension to the field boundary near the beck, using very large blocks of shather - soft, weathered stone - each of which bears a pecked hole to take the L-shaped quarry-dog crane hook. This suggests a period of mechanisation and great activity, probably after 1878, when the railway reached Thornton. The awkward gap between this east-west wall and the section higher up the road was at some time infilled with stepping, drystone buttress walls on which trees were planted between 1891 and 1909. John Farrar & Sons opened up Black Dyke Lane quarry between 1890 and 1900 and tipping resumed on the site of the old Bell Dean quarries, continuing well into this century.10 Egypt quarry also maintained its production of good stone and many people still remember the sound of the sawing-sheds.

Harry Speight, writing in 1890, seems to confirm that the Walls of Jericho were then complete.11 He refers to the secluded hamlet of Egypt with its Methodist Chapel, the several quarries in the area and the road which "winds through a narrow walled pass and ascends to Black Dike Lane at the Rock and Heifer Inn". Walks Around Bradford (1909) describes the reverse journey, down to Egypt.

"The great thing about it is the road thither, which presently drops down dramatically between two veritably cyclopean walls of rejected quarry stones… Emerging from these romantic and imposing portals the wayfarer discovers Egypt to consist of three cottages and a chapel."12

The Walls of Jericho have stood as silent, solid witnesses to long years of quarrying at Egypt, but their days are numbered. In 1982 they were declared unsafe and the road was closed. Faced with a bill of £500,000 for urgent repairs the West Yorkshire County Council applied for permission to demolish the walls, and after a public inquiry Patrick Jenkin, the Environment Secretary, granted listed building consent for the demolition. A new road is to be built, and if there is no successful objection work will begin within five years.

References

1. W. Cudworth, Round About Bradford, 1876 (Mountain Press, 1968), p.140. (back)

2. E. Southwart, Bronte Moors and Villages from Thornton to Haworth, 1923, p.272. Illustrations, one being of the Walls of Jericho, are by T. Mackenzie. (back)

3. A.H. Smith, Place-Names of the West Riding, E.P.N.S., vol.32, pt.3, p.272. (back)

4. P.F. Kendall and H.E. Wroot, The Geology of Yorkshire, 2 vols., 1924, ii, p.898. (back)

5. Copy by Hugh Oldham, 1840. (back)

7. Bradford Central Library, THO 1876 PLA, Plans of Upper Kipping, Bell Dean and Moscow. (back)

8. Bradford Central Library, THO 1873 WOO, Plan of valuable freehold land, Thornton. (back)

9. 25in. O.S. Map, 1891. (back)

10. 6in. O.S. Map, 1909 ed. (back)

11. H. Speight, ('Johnnie Gray'), One Hundred and Eighty Pleasant Walks Around Bradford, 1890, p.27. (back)

12. Anon, Walks Around Bradford, 1909. (back)

(This article is an extract from a much more extensive piece of research made by Miss Armstrong into the geology of the region.)

© 1985, Alison C. Armstrong and The Bradford Antiquary