The Masons Arms

A Study of a Bradford Beerhouse

Paul Jennings

(First published in 1989 in volume 4, pp. 61-66, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

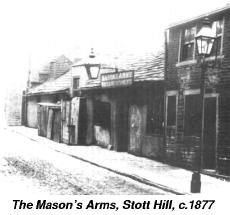

A hundred years ago the Masons Arms in Stott Hill closed its doors for the last time, to be demolished for street improvements. The photograph reproduced here, taken not long before the end, is a rare and evocative reminder of an institution which was so essential a feature of Victorian life, the public house. However, in his discussion of leisure pursuits in Bradford, David Russell noted, with considerable understatement: '… the social history of the public house is not yet fully explored'.1 This article forms part of a continuing endeavour to set matters right. Using the Masons Arms as a case study, I shall attempt to throw some light on various aspects of what is proving to be an extensive and fascinating project: the history of the public house in 19th century Bradford.

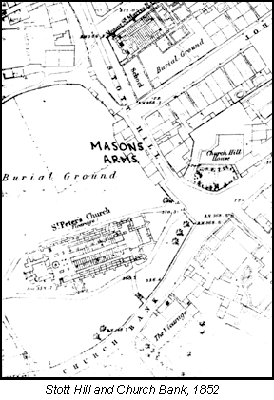

The Masons Arms was a beerhouse situated in Stott Hill at the top of the parish churchyard. It came into existence, like many others, through the Act of Parliament of 1830 which provided that, 'for the better supplying of the public with beer in England', any householder assessed to the poor rate could obtain from the Excise for a fee of two guineas, a licence allowing him to sell beer in his own home for consumption on or off the premises.2 It was no longer necessary first to obtain a licence from the justices, as public houses selling all types of drink were still required to do. The Act aimed to curb the excessive working-class drinking of spirits by encouraging the consumption of beer, which was regarded as more wholesome and less conducive to drunkenness and disorder. Nationally, within six months of the Act coming into effect, over 24,000 people took advantage of the business opportunity which it offered, and within seven years there were over a hundred beerhouses in Bradford.3 By 1860 there were 270, compared with 139 fully licensed houses, and. eight years later, just before the reintroduction of magistrates' control, the figure had risen to over 400, while the number of full licences was almost unchanged at 141.4

Robert Fearnley, one of the six children of Samuel and Elizabeth Fearnley, converted part of his property in Stott Hill into a beerhouse, in 1845.5 Elizabeth had inherited the property from her father, Robert Ward, who was the parish clerk. Her husband, Samuel, a stonemason, had built further houses on the land, making a total of eight and, on Elizabeth's death in 1835, the property was divided between her children.6 Robert followed his father's trade and continued to work as a stonemason after setting up the beerhouse, as the 1851 Census shows. The practice of following another occupation seems to have been quite common among beerhouse keepers. His wife, Hannah, probably played a major role in running the business, which would include brewing the beer. The name, Masons Arms, reflects not only Robert's trade, but that of several residents of the district, including other members of the Fearnley family.

Robert died in November 1860, but earlier, in February 1859, the beerhouse had been let to a man called Shaw Deighton, a currier of leather. His wife, Jane, also probably shared the work of running the business, and in addition they employed a servant, Mary Hutton. While Deighton was still the tenant, the whole property was sold by the executors of Fearnley's will, partly to pay off an outstanding mortgage, to Henry and Richard Priestley, a woolsorter and a butcher respectively, for £855. The beerhouse then comprised four out of the original eight houses, and Henry took over the management. Deighton moved only a short distance away, to the Church Hill Tavern, just around the comer from Stott Hill. (The public house of that name is now on the opposite side of Church Bank.)

Within two years, in October 1866, the Priestleys sold the property for £985, to Anthony Mitchell, who had been the tenant since August 1865. Mitchell had been a brewer and ostler before taking the Masons Arms at the age of about 28, and his previous experience probably explains why he continued to brew his own beer when other landlords were obtaining their supplies from the growing number of common brewers in the area. In 1869, of the 255 beerhouses in the Bradford Soke (that is within two miles of the Queens Mill in Mill Bank, and in the Manor of Bradford), 106 were listed as being supplied by a specific brewery, and a further 53 as selling only, no supplier being mentioned.7 The beerhouse-brewer was nearing extinction, for in the entire Bradford Excise collection area in 1894,just four remained out of a total of 832.8 Like the Deightons before them, and in common with most beerhouse keepers, the Mitchells employed a servant, according to the Census of 1871 an 18-year-old woman. They also had a 'nurse', aged only 12, to look after their three young children. Mitchell describes himself solely as a publican, probably reflecting the enhanced standing of the business, since by this time he was permitted to sell wine (under legislation of 1860) and was also licensed for music.

The public house was far more than simply a drinking place. Food was usually available, and people would sometimes take their own food and have it cooked on the premises. Some publicans offered board and lodging, as, indeed, many ordinary households did in those days. Entertainment was often provided by singers and instrumentalists, but the traditional games of darts and dominoes were played then, as they are now. When meeting rooms were scarce, public houses offered a warm welcome to all kinds of organisations, from friendly societies and sporting clubs to trade unions and political groups. We know that the Masons Arms was used as a committee room by the supporters of Henry Ripley throughout the infamous election of 1868. During that campaign the charwoman, Jane Rankin, helped to draw the beer, a great deal of which was described as going into the committee room, and on polling day, which began at 5 a.m., ham sandwiches and coffee were also available.9

From the beginning, beerhouses had been attacked, both nationally and locally, as being the haunts of thieves and prostitutes and the promoters of drunkenness. In response to such criticism, efforts were made, by means of further legislation, to curb any increase in their numbers. In Bradford the magistrates had also resisted attempts to extend the opening hours of beerhouses so as to bring them into line with licensed premises. As it was, they were allowed to open on weekdays from 4 a.m. to 10 p.m., and all day on Sundays, except during the hours of divine service. Not until 1869, however, was the Act passed which reintroduced the requirement of a justices' licence, a law which had a dramatic effect upon beerhouses.10 At the annual Brewster Sessions for the general renewing and issuing of licences, in August of that year, the justices carried out the Act, in the words of the local paper 'in its spirit and intent', by refusing a licence to some 60 beerhouses.11 Although the police records describe the character of Mitchell's house as 'indifferent' (the alternatives being simply 'good' or 'bad'), he was nevertheless granted a licence. The Stott Hill Tavern on the other side of the street was not so fortunate. Joseph Banks, the landlord, was refused on the grounds that prostitutes, thieves and beggars, and people from the nearby Old Hall, once a fine residence, but then a dubious lodging house known as 'Cadgers' Home', regularly went there.12

Mitchell died, aged only 36, in September 1874. His wife, Isabella, later married James Wooller, who joined her at the Masons Arms in February 1876. He left her, however, after three years, for in January 1879 she obtained an order of the Borough Court against him under the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, to protect her earnings and property, since he had deserted her without cause. She was not left alone though, as the Census of 1881 reveals a sizeable household. There was Isabella herself, described as a publican; six children, only the eldest of whom, William, an accountant's apprentice, was employed; her mother; a lodger, and a servant, 17-year- old Mary Smith from Knaresborough.

It was Isabella and William who were soon to sell the property, because in 1873 the Corporation had obtained Parliamentary authorisation for a number of street improvements, including the widening of Stott Hill.13 Under this Act it purchased the whole of the Masons Arms property, that is the original eight houses, for £2,350, a sum which included all claims for trade compensation, as well as furniture, fixtures and fittings. Demolition did not take place immediately however. Instead, the Corporation leased the public house to Isabella for £94 a year, under the usual terms for such an arrangement. These consisted of quarterly payments, and an undertaking that the tenant would 'conduct the said inn in a proper manner conformable to all local and general laws'. If the licence were lost or endorsed for any misconduct, then that amounted to notice to quit. In addition to this information the tenancy agreement contained a most interesting inventory of contents.14

The beerhouse itself consisted simply of two rooms, served from a small bar. Entrance from the street was through double glass doors into a passage lit by a fancy gas bracket and globe. There was a five-pump beer engine at the bar-counter, beneath and behind which was shelving for glassware and other utensils, among which were:

| 60 tumblers | 17 wine glasses | 21 pint pots |

| 6 quart jugs | 2 gallon jugs | 2 ½ gallon jugs |

| 6 pewter measures | 1 cut glass decanter | 1 filter |

| 2 funnels | 2 beer cans | 3 trays |

| a three-stand cigar holder |

In the bar parlour, which was partitioned off, there was seating around the room and, in addition, eight stools, a form, five tables and nine spittoons. The walls were bare, apart from two pictures and a large mirror, but there were venetian blinds at the windows. The rooms were lit by gas. Although the parlour was usually the most comfortable room in a public house (the 'best room'), at the Masons Arms the tap room was similarly furnished. In addition to wall-seating there was a form and two tables. Seven pictures, a pair of buffalo horns and a dartboard adorned the walls, and in an age of clay pipes and cheap tobacco the tap room was supplied with twelve spittoons as a safeguard against 'random expectoration'.

The Masons Arms was probably typical of the small beerhouse of its day, for as the clerk to the licensing justices later commented in his evidence to the Royal Commission on Liquor Licensing Laws, 'many of them were simply old cottages which never were fitted for the purpose of a public house of any kind'.15 The drinkers on Stott Hill were clearly not deterred by the hazard presented by the church's overcrowded burial ground, which had been repeatedly condemned as a danger to public health.

Another item in the inventory was the brewhouse, fully equipped, suggesting that Isabella continued to brew until the end. But brewers were gradually taking over, either by leasing or buying businesses outright. By 1890, 183 out of a total of 501 licences in Bradford were owned by brewers, the three largest being Whittaker's with 44, Waller's with 40 and Hammond's with 37. The owner-publican had become so rare that only eight were left.16

Isabella's brief tenancy ended in 1888 when the Masons Arms closed and was demolished, a fate which has overtaken numerous old public houses. Most recently the construction of an inner ring road extension has caused the loss of the Great Northern, Wakefield Road and the former Flying Dutchman in Leeds Road, which were both beerhouses originally. Perhaps more serious from a historical and architectural point of view was the demolition of the Junction Inn at the bottom of Leeds Road. All the more surprising then is the fact that amid a succession of upheavals in the city centre the Jacob's Well has stood its ground, being one of only three of Bradford's surviving beerhouses dating from 1830, the year of the Act which brought them into being.17

The end of the Masons Arms was not the end of Isabella. In October 1892 she took over the Church Hill Tavern, where she remained until October 1909, but she had then given up brewing because, in July 1891, Tordoffs Brewery of Thornton Road became the owners.18 The Church Hill (after a period of confusion with Churchill, the man), perpetuates one former beerhouse, but a photograph is the only visible reminder of the Masons Arms.

References

1. D. Russell 'The Pursuit of Leisure', in D.G. Wright and J.A. Jowitt (eds.), Victorian Bradford, 1981, p.218 n.13 (back)

2. An Act to Permit the general Sale of Beer and Cider by retail in England II Geo 4 and I Will 4 c64 (back)

3. S. & B. Webb, The History of Liquor Licensing in England, 1963 p.124, and White's Directory l837 (back)

4. Temperance Reports, Deed Box 16, Case 39, No. 4, W(est) Y(orkshire) A(rchive) S(ervice), Bradford (back)

5. See Register of Beerhouse Keepers 1860-69 A 124/110, WYAS, Wakefield. This forms part of the records of the former Bradford Borough Police and may be viewed with the permission of the West Yorkshire Police, to whom I am grateful. (back)

6. Title Deeds of Masons Arms, Bradford Council, D 968. Quoted by permission of Director of Legal Services (back)

7. Records of the Bradford Soke District, in records of the Bowling Iron Works, WYAS, Bradford. (back)

8. Return of Brewers Licences P.P. ,1895 (c96), vol. 88 p.87 (back)

9. See, Bradford Election Petitions Report of the Proceedings. Against the Return of Henry William Ripley Esq. and the Rt. Hon. W.E. Forster as Members for Bradford, 1869, p.20 (back)

10. Wine and Beerhouse Act 32 & 33 Vict c27. See also my Inns and Pubs of Old Bradford, l985 and Studying Beerhouses in the Local Historian vol. 17 no. 8, 1987. (back)

11. Bradford Observer, 31 Aug. 1869 (back)

12. ibid. 27 Aug 1869. The 'fine residence' was Stott Hill Hall, which dates from 1660, when it was occupied by the Rev Jonas Waterhouse Vicar of Bradford. In 1791 it was purchased by Joseph Priestley, who became superintendent of the Leeds-Liverpool Canal Company. It was demolished in 1877 (See Bradford Antiquary pt. 25, 1932, p.193) (back)

13. Report of the Street Improvement Committee, in Reports of the Committees of Bradford Council, 1877, p.46 (back)

14. Bradford Corporation Register of Agreements 53D 82/2/340, WYAS, Bradford (back)

15. Royal Commission on Liquor Licensing Laws P.P. l897 (c8356), p.375 (back)

16. Home Office Return of On Licences, P.P., 1890-1 (c28), vol. 68 p.107 (back)

17. By Bradford I mean the origina1 borough area. The others are the New House at Home, Little Horton Lane and the Admiral Nelson, Manchester Road though the latter is not the original building. (back)

18. See Bradford Borough Register of Licensed Beerhouse Keepers in records of Bradford Borough Police, A 124/111 WYAS, Wakefield, also J. & S. Tordoff Ltd. Trust Deed 1901 54D 80/13/3, WYAS, Bradford. (back)

© 1989, Paul Jennings and The Bradford Antiquary