Occupations in Eighteenth Century Bradford

Elvira Willmott

(First published in 1989 in volume 4, pp. 67-77, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

At the beginning of the 18th century Bradford was a small market town with a population of just over a thousand, or twice that number if the neighbouring townships of Bowling, Horton and Manningham were included. During much of the century it was a self-contained, fairly isolated place, in which nearly everyone knew everyone else, a fact that clearly emerges from the Examinations in the Quarter Sessions records, where few wrongdoers escaped identification. But Bradford also made contact with the wider world through wool buyers who went into Leicestershire and Lincolnshire; and when Ivebridge required repair in 1741 it was described as 'standing in a great high road between London and Kendall'.1 In October 1745 the church bells rang out to welcome a regiment of Royal Scots as it marched through the town,2 showing that Bradford was not left entirely unaware that great national events were taking place. Communications were greatly improved by turnpike roads, by means of which Bradford had been linked with other Yorkshire towns since 1734, and the Bradford Canal, opened in 1774, brought traffic from the great waterways to its door. By the time of the first census in 1801 the four townships combined had a population of 13,264.

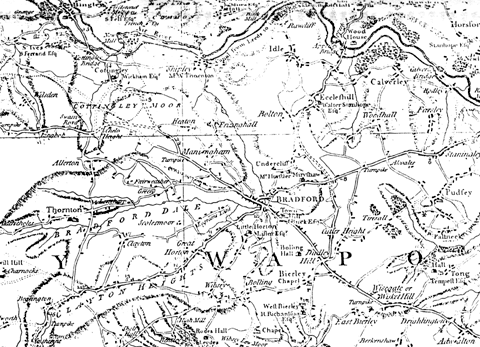

From a map by Thomas Jefferys, 1752

Information about male occupations during much of the century can be obtained from the Bradford baptism registers, which show fathers' occupations from March 1713 until the early 1740s, starting again in March 1775.3 The details given indicate the general trend of employment and in almost all cases the township in which a man lived is recorded. References to occupations in such sources as Quarter Sessions records, deeds and wills, are sparse, and there are no Corporation records until 1847, when Bradford received its Charter. Unfortunately very few of the earlier township records have survived. In this survey four seven-year periods have been examined, using baptism registers from 1714 to 1720, 1734 to 1740, and 1775 to 1781, and marriage registers from 1754 to 1760.

The rise of Nonconformity in the area during the 18th century meant that some children would not have been baptised at the parish church, although from 1714 to 1720 the number was probably very low. The Presbyterian chapel in Chapel Lane was built in 1717, at about the same time as the first Quaker meeting house in Goodman's End, where ten children were baptised. Small Baptist groups met in Heaton and Rawdon, but it was not until 1753 that a church was officially formed in Bradford, with meetings at the Cockpit. In 1743 the Vicar of Bradford estimated that a sixth of the parish were Dissenters, that is Quakers, Presbyterians and Baptists,4 so that proportion of baptisms (about 17%) can be expected to be missing from the sample between 1734 to 1740.

As we have said, for the period from 1754 to 1760 marriage registers have been used. Hardwicke's Marriage Act of 1753 specified that all marriages, except those of Jews or Quakers, should take place at the parish church of one of the parties, although in practice some Roman Catholics refused to be married in Anglican churches. In neither the Archbishop's Visitation of 1743 nor that of 17645 are there are references to the presence of Jews or Roman Catholics in Bradford, and although there were some Quakers their numbers were not large. However, some marriages must have been celebrated in the parish of a non-Bradford bride. Between 1754 and 1760 there were 85 marriages of non-Bradford men to Bradford brides recorded in the Bradford marriage registers, so a similar number of Bradford men might be expected to have married outside the parish, of whom about a third may have been from Bradford, Bowling, Horton and Manningham. Thus about 28 (8%) of marriages might be missing from the sample. By 1775 the number of Dissenters had increased, because at the Visitation eleven years earlier it was said that there were 1811 such families in the part of the parish not covered by the chapels-of-ease, of whom 103 were Methodists, 187 Presbyterians, 171 Baptists, 32 Quakers and 4 Moravians. Excluding the Methodists (whose children may have been baptised at the parish church) 394 (22%) were unlikely to have conformed. By the 1770s this proportion had probably increased to at least 25%.

Thus the data for 1714 to 1720 are almost complete, while those for 1734 to 1740 omit about 17% of possible occupational information, those for 1754 to 1760 about 8% and those for 1775 to 1781 about 25%. It is not possible to establish that the occupations and the proportions in which they were followed were the same in the missing baptisms and marriages but there is no reason to suppose that they would have been different.

Information has been collected only for men from the townships of Bradford, Bowling, Horton and Manningham which were to form the borough of Bradford in 1847. All their marriages have been used as it is unlikely that many men would marry more than once in seven years. Men having children baptised should appear only once in each set of years as second and successive entries for men with the same name and occupation have not been taken account of. However, if the same name appears twice with different occupations it has been counted twice, unless the occupations are virtually identical, e.g. cordwainer and shoemaker. If the same name and occupation appears in more than one township it is counted more than once. There are very few occasions when no occupation is given. It is important to note that the name of the mother, which would help to distinguish men with the same name, is never given in the Bradford registers of these dates. Men whose names are taken from the marriage registers were more likely to have been younger than those already married and presenting children for baptism, and this might affect the occupations they followed. It should also be realised that rootless or very young men will probably not appear in either set of figures as they were unlikely to marry and raise families. (Baptism entries for children born out of wedlock nearly always give the mother's name only but not her occupation.) Men who did not marry or have their children baptised are also missing from the returns. There is a small possibility that some men will appear more than once, perhaps having children baptised in different periods, or marrying in one period and having a child baptised in another. No attempt has been made to find such men and exclude them.

A man's occupation does not necessarily show his place in the economy or in society: a tanner, for instance, might own a considerable business or be a poverty stricken employee. Nor do the registers throw any light on occupations followed by women and children, or the dual occupations of some men. Much of the spinning was done by women and children, and many men shown as clothiers or weavers would probably be engaged in subsistence farming too. The occupational categories are those used by May Pickles in an article on mid-Wharfedale in the 18th century. Mrs. Pickles, who used parish registers as one of her major sources, covered the dale from Conistone down to Otley, giving the figures for Otley separately.6 Otley, like Bradford, was the centre of a large rural parish. Their populations were roughly the same and both towns were about nine miles from Leeds. The categories are land, landless labour, coalmining (replacing Otley's leadmining), textiles, clothing and footwear, food and drink, building, minor trades and industries, services, professions, gentry, servants and militia.

The proportion of men employed in agriculture (shown in the registers mainly as yeomen, farmers or husbandmen) was low, although, as might be expected, slightly higher outside Bradford. The figures for Bradford remain more or less constant between 1% and 3%, and those for the other townships rise from 3% to 6%. These percentages have been obtained from a small number of men and may be subject to distortion on that account, but as they are consistently low for all the townships it is likely that they indicate the true position. In a survey of the West Riding published in 1794 the authors said that adjacent to the manufacturing towns most of the land was occupied by people 'who do not consider farming as a business, but regard it only as a matter of convenience'.7 Such men did little more than keep cows for milk and horses for carrying goods to market.

It is impossible to say how many of those recorded as landless labour (usually shown in the registers as labourers) were in fact working on the land, or how many men shown, for example, as clothiers, were also concerned with agriculture. But even if the total land and landless labour categories are combined, only at the beginning of the century do they exceed 25% of the sample, dropping from 27% to 8% in the middle and later sections of the century. The figures for Bradford alone show the position of agriculture as an employer of labour more clearly: when combined, the two categories never rise above 17%.

Most of the land in the four townships is between 300 and 600 feet above sea level, and because of poor soil and an uncooperative climate agriculture has always been difficult. From early times this must have limited the size of the population that could be supported. Growing specialisation and improved transport, however, made it possible to obtain produce from other places, such as the Vale of York.

Coalmining, which was not a large occupation, was concentrated in Bowling, where by the late 1770s it provided employment for 13% of the sample examined. There were some miners in Bradford and Horton but hardly any in Manningham. Some men with other occupations, especially those who owned land, had connections with mining. The will of Jeremy Thornton of Horton, woolcomber, for example, refers to a close in Bowling owned by him and including 'coals, mines, veins and quarries of coal'.8

The presence of coal in the area was to have considerable significance when steam was introduced and coal became an industrial fuel, supplies of which could be cheaply transported by barge after the opening of the Bradford Canal in 1774. The preamble to the Keighley Wakefield Turnpike Act of 1753 refers to heavy carriages, laden with coals, using the roads in the Bowling area,9 but until about 1775 coal seems to have been mined on fairly small scale for use mainly as a domestic fuel.

Textiles predominate nearly all the time in Bradford and Manningham and in the other two townships for all periods except the first. Initially the percentages are similar: 25% in early Hanoverian Bradford and 28% in the townships combined, but in 1734 to 1740 Bradford has 28% and the others 50%. As the century progresses the trend continues, until by the final period, the late 1770s, Bradford has 47% and the other townships have 73%. Bradford thus remains a town with over half its male population engaged in non-textile occupations at all times. Such a result, showing a more diversified occupational structure, is consistent with Bradford's position as a market town and the centre of a large and scattered parish. Of course some of its other occupations, such as those of carriers and tailors, were connected with textiles, and these figures necessarily exclude all reference to women and children, whose spinning must have contributed considerably to the local economy.

As the proportion of textile workers increases there is a change from woollen to worsted production, a change more marked in the other townships than in Bradford. This change has been identified by noting the actual occupations mentioned in the parish registers. Some, such as woolsorter and shuttlemaker, were common to both types of production, but others indicate which branch was being followed. Clothiers, clothmakers, feltmakers, clothdressers, a wool dresser, a cloth presser and cardmakers have been regarded as producing woollens, while weavers, (wool)combers, stuffmakers, piecemakers, worsted men, combmakers, merchants and woolstaplers have been treated as worsted workers.

Omitting those occupations which could belong to either branch, the percentage of worsted workers in Bradford as a proportion of all wool textile workers rose from 10% at the beginning of the period, through 22% to 76% at the end. In the other townships the percentage rose from 20% through 51% to 94%. These figures show a particularly large increase between the periods 1734 to 1740, and 1754 to 1760, but they may well have been affected by the fact that the figures in the 1730s are for fathers presenting children for baptism, while the figures in the 1750s are for the presumably younger men who were marrying. It is reasonable to assume that the younger men were more likely to have made the change to a newer form of textile production.

These figures agree with the finding of scattered references to worsted workers in the Halifax and Bradford areas from the beginning of the 18th century and with the steady increase in worsted production which followed. By 1741 the Yorkshire trade rivalled that of other places, chiefly the Norwich area, and between 1750 and 1760 worsted production increased in the West Riding, especially in Bradford and Halifax.10

So marked was this increase that in 1773 two merchants and seven stuffmakers, acting on behalf of their fellows, promoted the building of the first Piece Hall in Bradford, followed in a very few years by a second, associated hall. In these halls, the first containing 100 stands on the lower floor for subscribers as well as space on the upper floor for non-subscribers, and the second containing a further 158 stands, manufacturers could expose their goods for sale. Previously they had either used rooms in their own houses, or, if they lived outside Bradford, had rented stands in a room at the White Lion Inn.11 Alternatively they could have attended Wakefield where the Tammy Hall was opened in 1766. A Piece Hall was erected at Colne in 1775 and at Halifax in 1779. The woolstaplers who organised much of the worsted trade were unable, individually, to suppress the various frauds and embezzlements practised against them, and consequently a Worsted Committee was established in 1777 to control such activities. Four Bradford men were on the first committee and its first chairman, John Hustler, was a Bradford man who had been prominent in the fight to establish it.

This change from woollens to worsteds must have gone hand in hand with a change in the status of the men working in the trade. The clothiers, whose prominence declined from the beginning of the period (83 in 1714 to 1720 and 4 in 1775 to 1781) would have been men who, with the aid of their families and possibly a journeyman or apprentice, carried out most of the necessary processes before taking the cloth to be sold. Such men would have had a fair degree independence. In making worsteds it of was usual for one man to buy wool and arrange for others to comb, spin or weave it. He would incur higher initial expenditure and would wish to exercise control over the various processes, perhaps saying how long each should take or imposing other conditions over the quality of the work carried out. The combers or weavers who did this work were very little more than his employees. Moving on to clothing and footwear we find that this category consists almost entirely of tailors, hatters and shoemakers or cordwainers (here defined wholly as shoemakers, although it is possible that some of them were leather workers). Shoemakers and cordwainers, the providers of a basic item, were in the majority, especially later in the century, and they and the tailors were represented almost everywhere at all times; hatters only appeared in Bradford. In the first two periods a substantial proportion of the population was employed in this category: 19% and 20%. By the final period the proportion was down to 10%, although the actual number of men involved was much the same. In Bradford there appears to have been a little specialisation, with a glover appearing in 1734 and a breeches maker in 1758. There was a clear concentration of men in clothing and footwear in Bradford, implying that those living outside used the facilities provided in the central and larger township.

This is a trend which is shown equally clearly in food and drink. Almost the only occupations of this kind shown in the outer townships are butchers and millers, both dealing in basic foods. There is one maltster in Horton but the others are all in Bradford. At this time most beer was brewed in small quantities, but common brewers, who produced large amounts of beer, began to appear in Bradford in the mid-18th century. Bradford's first brewery, that of Aked and Storey, was established just over the border in Horton in 1757.12 Bradford appears to have had all the inns, but one or two are shown in Manningham towards the end of the century. A few innkeepers appear in other sources, and there may have been ale-houses, but none of those who ran them appear in the registers which have been examined.

Eighteenth century inns in some towns were more than places providing food, drink and accommodation. They could be centres of commercial, administrative and social activity with trading facilities, such as storage and banking. They were often places where local justices and parish officials held their meetings, proving specially important when elections were held, as well as being convenient for lectures, concerts and plays.13 It has already been seen that a Bradford inn was used to display worsted pieces for sale before the Piece Hall was built, and Quarter Sessions records show that the justices, when in Bradford, often met in local inns.

The proportion of those engaged in building and similar activities (mostly shown as masons, carpenters and joiners, with a few plasterers and even fewer brickmakers and slate rivers) remained remarkably constant during the century. It would be difficult to use these figures to argue that a building boom took place, although the actual numbers increased throughout the period. It is unlikely that those men shown as joiners and carpenters were employed only in building, because wood has always been in very general use and articles of all kinds would have to be made and repaired. Rather more people were employed using stone near the beginning of the century, while more wood users appear towards the end.

The contrast between Bradford and the other townships is even more marked when minor trades covering such occupations as blacksmiths, coopers and tanners are considered. Bradford, where the percentages range from 11% to 15%, was clearly the centre for such occupations, while in the townships the proportion lies between l% and 5%. Because of the low numbers outside Bradford it is difficult to draw firm conclusions, but with the exception of blacksmiths, who provide 8 out of 32 recorded miscellaneous trades of this nature, other employment is very poorly represented in the townships. Very few occupations, and those all in the last period, are recorded in the townships and not in Bradford.

Nailmakers are, perhaps surprisingly the most numerous of those employed in, minor trades, with 29 occurrences throughout the century. When combined with the 13 recorded wiredrawers, who drew metal out into wire in order to make it ready for the nailmakers to use, their preponderance is even more marked. The first of several ironworks in the Bradford area, Emmet's at Birkenshaw, was not established until 1782, so supplies of iron for the nails probably came from Kirkstall forge where a slitting mill was in operation from 1678.14 The nail trade was easily learnt and required only a small amount of capital, and in the Ecclesfield and Sheffield areas it was frequently combined with part time farming.15 In 19th century Silsden it was also combined with farming.16 This could have been the case in eighteenth century Bradford. It would seem that such a large number of nailmakers was producing more nails than would have been required by the local carpenters, joiners, shoemakers and blacksmiths revealed by the samples, and that nails were being made for a wider area.

Coopers, whitesmiths, ropemakers and tanners followed occupations which one would expect to find in a local centre like Bradford, where some agriculture was carried on, but where textiles were becoming increasingly important. Wood for the coopers was available locally and leather for the curriers, tanners and fellmongers would come from local animals, but tin for the whitesmiths must have been obtained from outside the area. Although most of the occupations were everyday ones, the clockmakers introduce a measure of sophistication, as do the locksmith, two tobacconists and two cabinet makers first shown in Bradford only in the 1770s. Those who could afford luxury goods probably obtained them from Leeds which was developing into a regional centre; its recorded occupations up to 1779 include a goldsmith, silversmith, upholsterer, wine merchant and musician.17 It was in the fourth period that several combmakers first made an appearance, not combs for the woolcombers which are included in the textile category, but combs made of horn and ivory (respectively four and three makers). Crosby's Directory of 1807 refers to the making in Bradford of large quantities of horn and ivory combs.18

Three lime burners appear for the first time in 1775 and 1780, their presence being almost certainly due to the formation of the Bradford Lime Kiln Company in l774,19 whose kilns were built alongside the Bradford Canal, which was opened in that year to connect Bradford with the Leeds Liverpool Canal. By this means lime was brought down from the Craven hills into Airedale and the textile towns, where it was processed before being used both in building and as a fertiliser.

In services there is once again a concentration of jobs in Bradford, principally connected with transport and non-specialist retailing: 8% as compared with 20% in Bowling and Horton, and none in Manningham. There is also a greater variety of occupations in Bradford, particularly by the 1770s. Everywhere the carrier and the carter, augmented by two waggoners, a chaise driver and a coachman, are numerically the most important. This reminds us, if we are likely to forget, that in the movement of raw materials, products and people, horses were indispensable. The parish registers thus confirm the picture of a widespread carrying trade between 18th century towns drawn from the evidence of national directories.20 By the late 1770s four boatmen are shown in Bradford. Both they and two porters who appear first at this time were probably connected with the canal.

In 1720 the carrier living in Bowling is referred to as a London carrier, the only one to be so described, thus confirming the proposition that even in the early years of the 18th century the economy of England was more than purely local and regional.21 A postman is shown in 1715. Occasional references to Bradford postal services appear from the late seventeenth century onwards. Mail for Bradford was distributed from Ferrybridge, a post town on the Great North Road, and the postman would have been responsible for bringing letters to Bradford, not for delivering them within the town.22 By 1787 Bradford had a daily mail service to Leeds and Halifax, while that for London left every day except for Fridays, and that for Keighley operated on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays.23 There was provision for the local dissemination of news and announcements in the existence of a bellman in 1715.

A small number of retailers appear in the services category: several mercers and drapers and a hardwareman in Bradford, and badgers, a chapman, hawker and huxter in Bradford, Bowling and Horton. The occupations are again very much those required by a smallish working community, with only a hairdresser and two peruke makers arriving in the 1770s to give a touch of luxury - although there are also a few barbers throughout the century.

As with the other categories a sampling method such as that used here cannot show every occupation or the exact numbers of people following it, and the smaller the sample the more this is so. The service category in the Bradford figures examined ranges from 4% to 7% and in the other townships from under 1% to 3%. Some occupations known to exist in the middle of the century, such as that of bookseller and stationer,24 do not appear in the samples, confirming the suspicion that some people escape the net of the parish registers. This is even more the case when considering the professions, where the figures obtained from the registers are too few to give a complete view of the professional men in the townships: from under l% to 15% in Bowling and Horton. The figures which have been obtained agree exactly with those for the previous category with Manningham having no entries, and the others being divided between Bradford with 80%, and Bowling and Horton with 20% jointly.

There was a Vicar of Bradford throughout the period under consideration, and no doubt a parish clerk, as well as a number of nonconformist ministers, but it is only between 1734 to 1740 that two Anglican clergy appear in the sample, while a parish clerk only appears once and a single nonconformist minister is shown in the 1770s. A few schoolmasters and officers of Excise appear, spread thinly throughout the century, while there are two attorneys, two apothecaries and a surgeon. As Bradford grew, a few lesser professional men make an appearance: a book-keeper, clerk to the Court of Requests and a Sheriff's bailiff, as well as the master of the workhouse.

The category covering the gentry, interpreted as those described as gentlemen and Mr. in the parish registers, is even smaller. Never were there more than 2% in Bradford and l% in the other townships. In some cases this category is interchangeable with the previous one and with the top layers of some of the others. Lawyers and men prominent in other occupations are often shown in the parish registers as gentlemen.

Men employed as servants are shown in the Bradford sample only, and there were merely four of them in the periods covered. The number of military men is as small, with occasional soldiers in Bradford and Horton in the earlier part of the century, but rising to a peak of 6% in Bradford during the late 1750s, no doubt as at result of the Seven Years War of 1756 to 1763.

The occupational information which has been collected enables three main trends to be identified: the increasing proportion of textile workers, the change within textiles from woollens to worsteds. and the greater diversity of occupations within the township of Bradford.

During the first period covered (1714 to 1720) the textile category was the largest by a small margin in Bradford and Manningham, but it shared its prominence with landless labour in Bowling, Horton and Manningham, with coalmining in Bowling, and with clothing and footwear workers in Bradford. By the late 1730s it was noticeably pre-eminent in Bowling and Horton although less so in Bradford and Manningham. In the 1750s and 1770s it was much the largest category in the three outer townships, never employing less than 50%, while in Bradford it was the largest single category although it occupied just under half of the total workers. The balance changed from woollens to worsteds during the periods under consideration, especially in Bowling, Horton and Manningham. At first the percentages of worsted workers as a proportion of all definitely identified wool textile workers ranged from 10% to 26%, but by the 1770s the percentages were between 76%, and 98%. Of course, these figures omit females and children, but presumably they would have followed the same type of textile employment as the adult males.

The lower figure for textile workers in Bradford is balanced by the larger number of types of occupation and of men following them which were found in that township. In many categories, especially clothing and footwear, food and drink, minor trades and industries, and services this is very marked, with up to 80% of the total number of people in those occupations located in Bradford. Very few occupations appear in a township and not in Bradford, and Bradford, with a more broadly based economy, was clearly pre-eminent as a provider of goods and services of all kinds.

| 1714-1720 | 1734-1740 | 1754-1760 | 1775-1781 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land | 7 | 3% | 1 | - | 3 | 2% | 16 | 3% |

| Landless Labour | 37 | 14% | 30 | 10% | 5 | 3% | 35 | 6% |

| Coalmining | 7 | 3% | 3 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 12 | 2% |

| Textiles | 58 | 23% | 77 | 27% | 76 | 44% | 267 | 47% |

| Clothing & Footwear | 49 | 19% | 56 | 20% | 22 | 13% | 55 | 9% |

| Food & Drink | 13 | 5% | 25 | 9% | 5 | 3% | 26 | 4% |

| Building | 23 | 9% | 32 | 11% | 11 | 6% | 51 | 9% |

| Minor Trades & Industries | 31 | 12% | 42 | 15% | 21 | 12% | 65 | 11% |

| Services | 18 | 7% | 12 | 4% | 8 | 5% | 22 | 4% |

| Professions | 7 | 3% | 5 | 2% | 2 | 1% | 6 | 1% |

| Gentry | 2 | 1% | 1 | - | 4 | 2% | 4 | 1% |

| Servants | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1% | 4 | 1% |

| Militia | 2 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 11 | 6% | 9 | 2% |

| 254 | 286 | 171 | 572 | |||||

| 1714-1720 | 1734-1740 | 1754-1760 | 1775-1781 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land | 5 | 3% | 8 | 3% | 10 | 5% | 35 | 6% |

| Landless Labour | 66 | 36% | 47 | 19% | 11 | 6% | 15 | 3% |

| Coalmining | 25 | 14% | 11 | 5% | 11 | 6% | 40 | 7% |

| Textiles | 51 | 28% | 121 | 50% | 126 | 66% | 431 | 73% |

| Clothing & Footwear | 7 | 4% | 20 | 8% | 11 | 6% | 11 | 2% |

| Food & Drink | 8 | 4% | 3 | 1% | 1 | - | 7 | 1% |

| Building | 6 | 3% | 11 | 5% | 13 | 7% | 26 | 4% |

| Minor Trades & Industries | 8 | 4% | 11 | 5% | 5 | 3% | 9 | 1% |

| Services | 5 | 3% | 7 | 3% | 1 | - | 2 | - |

| Professions | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1% |

| Gentry | 1 | 1% | 1 | - | 3 | 1% | 3 | l% |

| Servants | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Militia | - | - | 2 | l% | - | - | 3 | 1% |

| 182 | 242 | 192 | 587 | |||||

References

1. Quarter Sessions Rolls July 1741 (Bradford) W(est) Y(orkshire) A(rchive) S(ervice): Headquarters QSl (back)

2. Bradford Churchwardens Accounts 1745 p.66 Bradford Cathedral 138. (back)

3. A microfilm copy of the Bradford parish registers at Bradford Central Library has been used. The original registers are at Bradford Cathedral. (back)

4. S.L. Ollard and P.C. Walker eds., Archbishop Herrings Visitation Returns, 1743, Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series 71, 1928 p.58 (back)

5. Archbishop Drummond's Visitation Return 1764 Borthwick Institute Bp.V 1764 Ret Vol. 1 (back)

6. M.F. Pickles, 'Mid-Wharfedale 1721-1821 economic and social change in a Pennine Dale', Local Population Studies, 16, 1976 pp.12-44 (back)

7. Rennie, Broun and Shirreff, General view of the agriculture of the West Riding of Yorkshire, (1794), p.13 (back)

8. Will of Jeremy Thornton. Pontefract Deanery Wills, September, 1749, Borthwick Institute (back)

9. 26 George II c.83 quoted in W. Cudworth, Histories of Bolton and Bowling, (1891), p.196 (back)

10. J. James History of the Worsted manufacture in England, (1857), pp.201, 231, 267. (back)

11. J.W. Turner, 'The Bradford Piece Halls' Bradford Antiquary, 1, 1884, p.136 (back)

12. E.M. Sigsworth, The brewing trade during the Industrial Revolution: the case of Yorkshire, (1967), pp.3, 10 (back)

13. A. Everitt, 'The English urban inn, 1560-1760' pp.104-120 of A. Everitt, ed., Perspectives of English urban history, (1973). (back)

14. R. Butler, The history of Kirkstall Forge through seven centuries 1200-1954, 2nd. ed., (1954), p.5 (back)

15. D. Hey, The rural metalworkers of the Sheffield region. a study of rural industry before the Industrial Revolution, (1972), p.34 (back)

16. F.W. Moody, 'The nail and clog-iron industries of Silsden in the West Riding' Yorkshire Dialect Society Transactions, 9, part 51, 1951, p.46 (back)

17. W.G. Rimmer, 'The industrial profile of Leeds, 1740-1840', Thoresby Society, 50, 1968, p.134. (back)

18. W. Cudworth, Historical notes on the Bradford Corporation, (1881), p.55. (back)

19. G. Firth, 'The Bradford Lime Kiln Company 1774-1800', Bradford Antiquary, 12, 1982, pp.129-133 (back)

20. G.L. Turnbull, 'Provincial road carrying in England in the eighteenth century', Journal of Transport History, N.S. 4, No. 1, 1977, p.37 (back)

22. D. Boyes, A postal history of Bradford to 1884 (1977), pp.10, 16 (back)

23. Sheet pasted into Abraham Balme's commonplace book, WYAS, Bradford DBl/6 (back)

24. W. Scruton, 'A Bradford worthy of the last century', Bradford Antiquary, 1, 1881 p.112 (back)

© 1989, Elvira Willmott and The Bradford Antiquary