The Battle of Bradford 1837:

Riots Against the New Poor Law

Paul Carter

(First published in 2006 in volume 10, pp. 5-15, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society.)

The Battle of Bradford 1837: Riots Against the New

Poor Law1

An early version of this paper was given to a meeting of the

Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society at the Bradford Central

Library on 21 November 2004.

At the 1838 Yorkshire Spring Assizes five men were indicted for a riot which had taken place at Bradford in the West Riding of Yorkshire on 20 November 1837. On that day a violent attack on the Bradford Court House occurred where the newly elected Bradford Poor Law Guardians were meeting. A large collection of ordinary Bradfordians were involved in the riot. At 10am the Bradford Guardians had met and various administrative poor law business kept them occupied until 2pm (the last hour or two the crowd and the guardians were kept apart by the military). During this time what was described as 'a very considerable crowd amounting to many thousands' gathered outside and around the courthouse. Military troops and special constables guarded the building. The crowd grew in number and confidence and at about 12 noon a group of the protestors forced their way through the doors to the court house and this appeared to be the signal for a hail of stones to be targeted on the building and the military guarding it. The riot act was read it would appear that there was a now continuous physical clash between the protesters and the troops. The guardians seem to have managed to leave the building with no serious problem, but John Reid Wagstaff, the clerk to the guardians, was 'detained' for several some hours. The windows of the court house were demolished. Wagstaff was rescued from the building by a troop of cavalry aided by two of the Bradford Magistrates. This group then made for the Talbot Inn but where followed by the crowd who then closed in on them. The military then charged into the crowd where 'several shots were fired and some persons cut down'.2

The riot on 20 November had followed an earlier riot on 30 October where huge crowds had attended the meeting of the Bradford Guardians. Alfred Power, one of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioners, was also in attendance at this earlier meeting and was assaulted on this occasion, being hit on the head by

a tin can, which was given with great violence, but being without weight, made only a slight contusion: umbrellas, stones and mud were applied very freely, and after meeting many blows I extricated myself with great difficulty from the crowd.3

What was happening in Bradford in 1837 was shared to varying degrees across much of England and Wales. This short essay is an attempt to place the Bradford events into a national context while remaining focused on events in the town.

The National Background

The growth of population, urbanisation and industrialisation in modern Britain from the 1730s and 1740s was dramatic. A nation domestically based on agriculture and rural populations was becoming one of industry and town/city dwellers. This in turn put great pressure on the Elizabethan legislation on how to ‘manage’ the poor. It was legislative changes to poor relief which prompted the events in Bradford in 1837. In 1832 the new Whig government appointed a Royal Commission to investigate the operation of the Old Poor Law,4 and recommend legislative changes to deal with poverty. In 1834 the Commission produced its report5 and within months the Poor Law Amendment Act was placed on the statute book.6 This was possibly the most important piece of social legislation ever introduced by any nineteenth century British parliament. Welcomed by many rate-payers in southern England and applauded by the political economists of an increasingly market orientated society the New Poor Law was seen as a scientific method to reduce poor rates and rescue paupers from their degraded state of pauperism.

The Old Poor Law had essentially set out three key responsibilities for local communities funded through money raised by a local tax on land. Firstly, the setting of the able-bodied to work; secondly, purchasing of apprenticeships (or some other training) for poor children; and thirdly, the relieving of the impotent poor. The responsibility was placed on the shoulders of the churchwardens and overseers of the poor in every parish, although in many large parishes in the northern counties this would come to be based on townships or other divisions. This local system was overarched by the supervision of local magistrates who agreed nominations of local overseers, audited their accounts and heard appeals against the decisions of the parish or township officers. Subsequent legislation modified and clarified the Elizabethan poor law, in particular the strengthening of settlement laws that determined which individuals had a call on the resources of which particular parishes.7 However, in the main, the basic system remained very much still intact in the early 1830s.

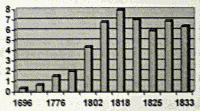

As relief was provided locally there was much discretion as to how relief was offered. Many parishes and townships allowed paupers to live in their own homes and paid simple doles to regular claimants and casual payments to those needing more ad-hoc relief. On the other hand payments could be made in kind; such as low cost or free rented houses, food, clothes, fuel etc. Some authorities built or purchased workhouses or poor houses and offered relief on an ‘in-house’ basis, while others 'contracted out' poor relief for an agreed sum of money. Relief was also expended on medical aid and purchasing tools or equipment to enable people to get/return to work. Indeed the longevity of the system reflects the flexibility that was afforded to those entrusted to administer and police the management of the poor. By the late eighteenth century parishes and townships had devised a wide range of local relief practises usually designed theoretically to manage a reduction of costs (although it usually meant 'managing' an increase). Indeed a disturbing feature of the poor law, from the point of view of the ratepayers, was the seemingly inexorable increasing levels of expenditure illustrated by fig. 1 below. As the poor law went into crisis in the late eighteenth century local initiatives took on a wider regional role that saw the widespread adoption of ideas outside of the specific locality. The most well known of these ideas was the provision of allowances from poor rates to workers who were unable to secure subsistence rate wages.8 Most of these loca8 schemes were criticised for bringing down wages and/or encouraging large families (and so further increasing the strain on the system). The continuation of high levels of expenditure saw continued parliamentary investigations of the operation of the poor laws, as well as continuing local experiments to reduce expenditure and an explosive outpouring of pamphlet literature suggesting various changes to the law.9

Fig. 1: Poor Relief Expenditure for England

and Wales

(£million), 1696-183332

It was the rural unrest in the south and south-east of England in 1830-31 which precipitated the Commission of Enquiry into the poor laws in 1832.10 The 'Swing Riots' promoted the desire for poor law reform and acted as a catalyst for government action. A general impression was formed that the riots, rick burning and machine breaking took place principally in those areas associated with the allowance system, and that rural militancy had followed there when unreasonable demands for 'parish pay' were refused. The Commission argued that allowances in aid of wages was a widespread 'evil' and should be abolished. Relief should be offered in regimented and rule-bound workhouses. To deter applicants the conditions in the workhouse should be 'less eligible' (less comfortable) than the conditions of the lowest paid labourer outside.11 The object of the nineteenth century workhouse system was to create a feared institution that the able-bodied would go to as a last resort.

Administratively the New Poor Law set up a central Poor Law Commission (PLC) with its headquarters at Somerset House in London. Three commissioners were to oversee the national poor law and impose national uniformity. Parishes were to be joined together in Poor Law Unions offering relief around a central workhouse and each governed by an elected board of guardians. Local magistrates, the supervisors of the Old Poor Law overseers, were now themselves only ex-officio guardians. The guardians would employ a master and mistress (and other staff) for the day-to-day running of the workhouse and each parish/township would continue to levy a parish poor rate that would fund the union. The act was thus designed to ensure that the provisions of the law were to be implemented efficiently by professional officials rather than parish amateurs. Although the act did not specify that relief to the able-bodied was to be abolished or that the PLC was to have authority to order a workhouse building programme, the principles of the 1834 report was the philosophy, dogma and blue print of the commissioners and assistant commissioners which would see such ideals represented as the necessary pillars for the Victorian plan of poor relief practice. A paradigm ideal was created by which a family applying for relief would be interviewed by the workhouse authorities and separated; men would be housed in one block, women in another and children in a third; all paupers to wear a standard uniform and their lives in the workhouse was to be humiliatingly regimented, ordered and structured.

Bradford: The Local Picture

By the 1830s Bradford was well on the way to becoming a key industrial player of nineteenth century British industrial capitalism. By 1800 Bradford could already claim a history of various industrial concerns. The owners of collieries, limekilns and ironworks had begun the employment of capital and labour on a new and larger scale. The Bradford Lime-Kiln Company, The Low Moor Ironworks, the Bowling Ironworks (as well as smaller ironworking concerns at Birkenshaw, Bierley and Shelf) and widespread eighteenth century shaft-mining across Bradford parish testify to early industrialisation.12 However, it is for worsted woollens that Bradford will be remembered in relation to the industrial revolution, and like all industries this grew from the material conditions in the locality. If the concerns of the wool and worsted industries were already a major part of the Bradford experience by this time through outworking and dual occupation working; the early nineteenth century was to see these concerns increase with a fierce intensity. In 1822 there were only five worsted merchants in Bradford. This increased to 24 by 1830 and 54 by 1842. In 1810 there were five steam-powered mills across the borough. There were twenty by 1820, 31 by 1830 and 34 in 1834 (the year of the New Poor Law). During the same period (between 1810 and 1834) the horse-power capability with these mills increased from 120 to 1,148.13

Industrial development had brought problems of economic dislocation and industrial struggles. Undoubtedly worried by the Luddite disturbances in 1811-13 across Nottinghamshire, Lancashire and the West Riding (though not in Bradford), a Bradford manufacturer secretly sought to construct a power-loom at Shipley in 1822. Secrets were not impossible to keep but the fear of wage reductions, under-employment and unemployment at the hands of new machinery meant that employers were unable to keep news of the introduction of such equipment into the area quiet. Local weavers from the outlying villages had the machine taken apart and destroyed.14 Following the repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824 a branch of what would become the Union Association of Woolcombers and Stuff Weavers was established in Manningham and this soon opened its doors to weavers. In June 1825 the Bradford worsted weavers and woolcombers embarked on a 23-week-long strike. Money was collected in neighbouring towns and villages, and also as far as south as Brighton and north into Scotland. Although unable to make any change to the terms of their pay and conditions the organisational links forged in the struggles of 1825 saw the union in good enough shape to take action again in 1827. The union seems to have folded in either 1828 or 1829 but at this stage the workforce threw themselves into the Yorkshire Clothiers Union.

By the early 1830s trade unionists and other factory reformers were increasingly involved in the campaigns to limit the hours worked in the still 'new' factories. Bradford was open to a deepening politicisation of the population aided by the town’s enfranchisement by virtue of the 1832 Reform Act. The parliamentary reform of 1832 gave no assistance to the Bradford workforce. Indeed the ascendant Liberals gained political power in the town and it was the Liberal textile industry employers who opposed the efforts of the short-time committees locally and elsewhere. Local meetings and campaigns for shorter hours (a ten-hour day) were common. Party and religious lines supplied the division of outlook. Liberal nonconformist employers opposed any change or interference from central government while Tory Anglicans, whether factory employers like John Wood or Anglican ministers like George Stringer Bull, insisted that market forces were an unjust and ungodly mechanism to decide the fate of the factory worker. Just how dedicated the local workforce was to reducing the hours of factory labour is illustrated by the York County Meeting organised to demonstrate for a 'Ten Hours Bill'. It was a cold and wet April in 1832 which saw people walking from the manufacturing towns and villages of Leeds, Bradford, Bingley, Huddersfield, Keighley, Dewsbury etc. to York to hear, support and demonstrate the case for factory reform. Banners were made with often religious or scriptural phrases. One showed a picture of a father carrying his small daughter through the rain and snow to work, another had inscribed the words:

"Father, is it time", a cry which is often heard the night through in the crowded wretched dormitory of the factory working-people, and which little children, more asleep than awake (dreading the consequences of being late), were often heard to utter.15

Such then was the developing economic local world into which the New Poor Law was introduced. Assistant Poor Law Commissioners were despatched into the rural south, local meetings were called, boundaries were organised and guardians were elected. By the spring of 1835 the first poor law unions were being declared. Opposition to the New Poor Law in the southern counties has often been underplayed but research shows how unpopular the new legislation was from the beginning and how, against the odds, ordinary people sought to oppose it. When the PLC turned their eyes to the industrial midlands and northern counties in 1836-7 this opposition took on new, militant, and politically organised resistance.16

The Old Poor Law in the various townships17 that would eventually form the Bradford Poor Law Union was practised under a variety of early administrative reforms.18 Neighbouring townships had been able to introduce such reforms (select vestries, paid assistant overseers etc.) with no requirement of agreement between them. However, these changes, whenever and wherever within the Bradford area, characteristically relied on a small proportion of permanent paupers (not including children) in receipt of indoor relief. Between 1812 and 1815 only 9.8% of such paupers were provided with indoor relief and this fell to only 6.3% by 1836. Local administrators were also able to point to low costs per head of population. Expenditure per head in 1831 at Bradford was 2s 11½d; in the rest of the west Riding 5s 7½d, Lancashire 4s 4¾d and Suffolk 18s 3¾d.19

When the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed in 1834 there was initially an element of a 'phoney war' opposition. The new administrative body in London needed to get its act together: premises needed to be made workable, procedures put in place, administrators employed. There was never any question of the whole of England and Wales being placed on a new poor law footing on any particular time. The greatest problems were identified in the southern counties and it was there that the first assistant commissioners met with local elites, employers and landowners to organise the first poor law unions. In the immediate New Poor Law period nothing really changed in Bradford. Nevertheless as early as 1 January 1835 the PLC received their first warning of the possibilities that things may not go well in Bradford. The following is taken from a letter to the PLC from Joshua Lupton.

Sirs.

A clergyman in this Parish having

taken upon himself the liberty of inflaming the minds of the Poor

against the Poor Law amendment act along with the Commissioners &

all persons in Office hereabouts – I as one of the Overseers

of this Township hand you a Bit of Paper by this

post, with a report of a Lecture delivered by the Revd Mr Bull last monday.20

He goes on to say that the editor of the Bradford Observer would give the PLC a right to reply should they wish to do so. The draft response to Lupton thanks him for the information on events in Bradford but declines to enter into any local public debate on the 'controversy as to the merits of the act which it is their duty to carry into execution now'.21 Although there was no immediate need for action against the introduction of the New Poor Law in Bradford in 1834 I have already commented on the political nature of the town in regard to the short-time organisation; in other words there was (before the 1834 act) already a broad-based working class organisation in the town. In addition to this the Bradford Political Union, which remained in existence due to the disappointment of the limited reforms of the 1832 Reform Act, eventually split in 1835 with the more progressive element forming the Bradford Radical Association. Initially members of the Bradford Radical Association were divided on the merits of the New Poor Law although this may have been due to the introduction of the act but the non-immediate introduction of its provisions locally. One of it's members, Peter Bussey, was in no doubts in his condemnation of the New Poor Law based on 'New Bastilles [which] were not intended as places of rest to the wearied and worn out operative, but ... were erected as places of punishment’.22 The two major political parties in the town (as nationally) complicated things for the radicals. The Liberals made friendly noises about extending the franchise but would have no truck with the short-time aspirations of the Bradford workers; the Tories were vocal in their condemnation of the conditions in the factories, the hours worked by small children and supportive of the short-time committee's objectives but were adamant that there should be no extension of the franchise. The division led Bradford radicals to favour abstaining from the election of Bradford Guardians in early 1837 and this left the Liberal forces taking control of the union. By October 1837 Assistant Poor Law Commissioner Alfred Power thought the New Poor Law would be relatively easily introduced into the town. However, the radical and working class opposition to the new system was very much present and Bussey had made sure that when the guardians were to meet with Power in attendance on 30 October the whole of the town would be on notice. The bellman was instructed by Bussey

to give Notice to the working Classes of this town that the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner will be at the Coart [Court] house in this town on Monday next at 10 O’clock in the Morning when the People of Bradford are Invited to Attend at ½ 9 o’clock at the Coaurt house.23

The call was answered and with large numbers of working class people in attendance the reassurances from the guardians fell on stony ground. Following a short adjournment there was 'great noise and confusion'. Power reported back to the PLC that when he left the Bradford court house at the end of the meeting he was 'violently assaulted by some of the persons assembled outside, and by others who immediately issued from the Court House for that purpose.' Power stated his relief that the crowd was unarmed 'or I believe, from the disposition shown, I should have not escaped with my life'.24 Power was incensed by the local police officers who he felt left him to the crowd. He complained they 'abstained from giving me any assistance at a moment when they must have inevitably have been aware that I stood in need of it'. The officers simply claimed that they saw no assault and would have expected Power to call for help if it was needed, neither being the case, in the words of Deputy Constable William Brigg 'I therefore remained in my office'.25

Power was concerned to ensure the implementation of the New Poor Law was not delayed in Bradford and called for the Metropolitan Police and the military to assist in its implementation. The Bradford magistrates were unhappy with the idea of using the Metropolitan Police, a force disliked by provincial populations and one likely to increase tensions. The use of such external forces divided the Bradford Guardians and Power later wrote to the PLC that

On the whole I think there is far more risk of the falling off of the Guardians [non-attendance or resignations of guardians] on the employment of a police force from London, than the dread of future disturbance.26

The result was that the contingent of one sergeant and six constables of the Metropolitan Police, who arrived in Bradford on 3 November, was initially sent to wait at Leeds, although a few days later two or three of them were called back to be used undercover to 'endeavour to obtain information as to the feelings of the people'.27 John Reid Wagstaff was concerned that the arrival of the Metropolitan force was both well known and openly ridiculed. He wrote to Power reporting that he had heard of people asking what chance the PLC and half a dozen London police had to 'control a Countryside'. Moreover 'the fact of their [London police] being known to be armed may induce numbers to come prepared to meet force'.28

How many took part in the riots on 20 November is difficult to determine. However, both sides claimed large numbers. Alfred Power considered it was 'a very considerable crowd, amounting to many thousands' who attacked the court house while the Northern Liberator spoke of 'large companies of persons [who] poured into Bradford from the surrounding villages.'29 The resistance to the New Poor Law saw a major, though short lived, series of disturbances in the town, and this was a key political struggle that initiated and maintained a series of radical meetings in and around Bradford. This activity places the town as one of the centres of a geographically wider opposition to the New Poor Law and sets the scene for northern Chartism towards the end of the decade. This is important because much of the class bitterness we see in Chartism in Bradford came from in the Anti-Poor Law agitations of the previous years. Indeed Edward Royle points to 1838-9 as the period when the Anti-Poor Law Movement moved over into Chartism, 'taking with it a legacy of organisation, leadership, experience, and hatred'.30 Thanks to the pages of the unstamped press and the lecture tours of radicals across the country, it is possible to argue that by the late 1830s a radical working-class presence existed across industrial Britain. It was in places such as Bradford that mid-nineteenth century British radicalism was forged.

Postscript

We return to the 1838 Yorkshire Spring Assizes where five Bradfordians were indicted for the anti-poor law riot at Bradford the previous year. The names of the men were Joseph Tillotson (who was also indicted for assault), Joseph Greensmith, Joseph Swain, William Brooke (sometimes Brook) and William Wheater; all but Wheater were convicted. Sentenced to one month in prison the men had also been in gaol throughout the winter of 1837-38.31 As part of the breadth and richness of Bradford history it would be nice to think that we do not forget those men who laid the ground for Bradford radicalism.

Notes

1. 'Beginning of the Civil War. - Battle of Bradford. - New Poor Law...' The quote is taken from The Northern Liberator, 25 November 1837. A full transcript of the article from which the quote is taken can be found in the Poor Law Union Correspondence for Bradford held at The National Archives (TNA) MH 12/14720, p 2 [item 109/folio 169] 2 December 1837. This volume has now been fully transcribed and indexed with full introductory chapters as P. Carter, ed., Bradford Poor Law Union: Papers and Correspondence with the Poor Law Commission, October 1834 to January 1839, The Boydell Press, 2004. (back)

2. Carter, Bradford Poor Law Union, p 70 [89/140] 20 November 1837; p 74 [94/147v] 20 November 1837 and p 80 [80/161] 21 November 1837. (back)

3. Carter, Bradford Poor Law Union, p 57 [114v-115] 30 October 1837. (back)

4. For the Relief of the Poor, 1601, 43 Elizabeth, c.2. (back)

5. Parliamentary Papers, Report… into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws, XXVIII, 1834. (back)

6. For the Amendment and Better Administration of the Laws Relating to the Poor in England and Wales, 1834, 4 & 5 William IV, c.76. (back)

7. In particular the

1662 Act For the Better Relief of the Poor of

this Kingdom [Act of Settlement] (13 & 14 Ch. II

c.12).

Settlement was originally determined by birth and

marriage for a woman. Newcomers to the parish could be removed by

two Justices of the Peace if complaint is made within 40 days that

they are 'likely to become chargeable'. However, this made it

difficult for labourers to find work outside their parish - it

was also difficult for employers required extra seasonal

labour. Certificates were introduced to allow a legal movement of

labour. (back)

8. J.R. Poynter, Society and Pauperism: English Ideas on Poor Relief, 1795-1834, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969, pp 76-85. (back)

9. Poynter, pp 272-94. The various positions and arguments for reform and abolition in the last four decades of the 'Old Poor Law' are set out in some detail in Poynter's book, which although published some time ago is still an excellent readable volume on the ins and out of the arguments. (back)

10. E. Hobsbawm and G. Rude, Captain Swing, Lawrence and Wishhart, 1969; M. Holland, ed., Swing Unmasked: The Agricultural Riots of 1830 to 1832 and their Wider Implications, Milton Keynes, FACHRS Publications, 2005. (back)

11. Report... of the Poor Laws, 1834, p 228. (back)

12. G. Firth, Bradford and the Industrial Revolution, Halifax, Ryburn Publishing, 1990, pp 97-140. (back)

14. W. Scutton, 'The History of a Bradford Riot', Bradford Antiquary, 3, 1884; and J.L. & B. Hammond, The Skilled Labourer, London, Longman, 1919, pp 194-5. (back)

15. Cole and A.W. Filson, British Working Class Documents: Select Documents, 1789-1875, London, Macmillan, 1965. Quoting from S. Kydd, The History of the Factory Movement, Vol. I. 1857, pp 325-6. (back)

16. See N.C. Edsall, The Anti-Poor Law Movement, 1834-44, Manchester U.P., 1971, J. Knott, Popular Opposition to the 1834 Poor Law, Croom-Helm, 1986; R. Wells, 'Resistance to the New Poor Law in the Rural South', in J. Rule and R. Wells, Crime, Protest and Popular Politics in Southern England, 1740-1850, London, Hambledon Press, 1997; R. Wells, 'Rural Rebels in Southern England in the 1830s', in C. Emsley and J. Walvin, eds. Artisans, Peasants and Proletarians, 1760-1860, London, Croom-Helm, 1985. (back)

17. Allerton, Bolton, Bowling, Bradford, Calverley with Farsley, Clayton, Cleckheaton, Drighlington, Heaton, Horton, Hunsworth, Idle, Manningham, North Bierley, Pudsey, Shipley, Thornton, Tong, Wilsden, and Wike [Wyke]. (back)

18. Carter, Bradford Poor Law Union, pp xxxii-xxxiii. (back)

19. D. Ashworth, 'The Poor Law in Bradford, c.1834-c.1871', A Study of the Relief of Poverty in Mid-19th-Century Bradford, Ph.D. Bradford, 1979, pp 45-6. (back)

20. Carter, Bradford Poor Law Union, p 3 [4/5] 1 Jan 1835. (back)

21. Carter, p 3 [5/6] 8 January 1835. (back)

22. Ashworth, Poor Law in Bradford, p 52. (back)

23. Carter, p 59 [117] 28 October 1837. (back)

24. Carter, p 57 [81/114v] 30 October 1837. (back)

25. Carter, p 65 [85/130v] undated; enclosed with letter dated 5 November 1837. (back)

26. Carter, p 63 [84/125v] 5 November 1837. (back)

27. Carter, p 67 [86/134v] 4 November 1837. (back)

28. Carter, p 68 [87/137] 10 November 1837. (back)

29. Carter, p 80, [160] 21 November 1837 and p 85 [169] 25 November 1837. (back)

30. E. Royle, Chartism, Longman Group, 1986, 2nd ed., 1986, p 16. (back)

31. Carter, Bradford Poor Law Union, pp 193-205, appendices 1 to 4 for details and transcripts of the relevant assize material. (back)

32. Figures taken from P. Slack, The English Poor Laws, 1531-1782. London: Macmillan, 1990, p 30; and B.R. Mitchell and P. Deane, Abstract of British Historical Statistics, Cambridge U.P., 1971, p 410 (back)

© 2006, Paul Carter and The Bradford Antiquary